INTRO: Launching a solo stand up paddle expedition is becoming a rite of passage for many serious paddling enthusiasts. Finding a body of water or land to circumnavigate, traveling along the coast of one’s home territory or even crossing oceans, like Casper Steinfath did in crossing the Kattegat Sea of Denmark, puts one on both an outward and an inward journey. We love the stories of these solo expeditions, like Lou Anne Harris paddling the length of the Mississippi River (see SPRING’20 issue), and Casper Steinfath paddling around mainland Denmark (happening now) through storm, sleet and snow.

Here, a young woman named Mariele Guerrero chooses to take on the challenge of paddling around her native homeland of Nova Scotia. What she discovers along the way is a bit of a hero’s journey as she relinquishes her end goal in order to be present in the poignancy of the moment. We salute the paddlers taking on these greater challenges. We look forward to sharing more of these stories, and perhaps inventing a few of our own…

Expedition SUP Mi'kmaw'ki: Paddling Around Mainland Nova Scotia

One of the most beautiful things about expeditions is that each embodies a unique spirit. Each comes with its own challenges, obstacles, and unforeseen blessings to teach lessons, derail expectations and open minds to the incredible strength and beauty of the natural world that lies around us every day. We just need to remember to open our eyes to it.

Last summer, optimistic and untethered by the ephemeral nature of passage on the Atlantic, I set out with a goal of circumnavigating the entire province of mainland Nova Scotia, solo by stand up paddleboard. Nova Scotia, also known as Mi'kmaw'ki, is the unceded and ancestral land of the Mi’kmaq people.

My expedition began on the Atlantic shore. I set off in early June with a fully loaded touring board secured with a 5m ratchet strap and four self-installed tie-down points. I was carrying all the gear I needed. The bow contained a 65 liter drybag packed with a full set of ultra-light camping gear, twelve days of dehydrated food, a robust repair kit, first aid kit, extra copies of my trip plan, and neatly fastened to the top of the bag, a 1:40000 scale chart. A 30 liter drybag occupied the stern, containing two 6L dromedaries and a two-piece powerblade paddle. Lastly, neatly tucked in my PFD, were two of my most critical tools and only lifelines, a hand-held VHF radio and satellite communication device.

As I sat on the beach waiting for the right moment to push beyond land, fear, self-doubt, excitement, and swirling thoughts of everything that could possibly go wrong danced in my head. In the months leading up to this expedition, my planning and preparation had become a full-time job. For five weeks I was married to my dehydrators, diligently changing trays every 6-12 hours, packaging meals, and sending them through the vacuum sealer. With the help of a friend, I spent months scouring Google Earth and gathering a thick stack of nautical charts for route planning, anticipating obstacles, and scouting for campsites and food drops along the way.

Despite my months of meticulous planning, on that morning the only comfort I could find was in the familiar sounds of the flowing tide splashing against the gravel shoreline and the distinctly salty smell of seaweed rotting on the rocks. With a swift push away and a gentle leap onto my board, I relinquished control of the outcome of circumstance. It was my choice to let the ocean be my guide, and I placed my trust in my own capacity to adapt to the dynamic ambivalence of the many states of the sea.

Characterized by surf breaks, thick fog, persistent South Westerlies, exposed headlands, deep bays, and small sections of pristine, protected archipelagos, the Atlantic section of the Nova Scotian coastline is harsh, exposed, and full of contradictions. The only certainty of travel along this coast was the inherent uncertainty of its rapidly changing weather systems.

In the early hours of the morning, the sea offered its most viable windows of passage. The rising sun danced on the horizon, painting the gentle Atlantic hues of pink and blue in the sky's reflection. Mild swells rolled through with perfect timing, quietly roaring as they crashed into the sloping granite shore. It was a beautiful contradiction to see an environment so harsh in such a peaceful state. But in those moments, while I found myself surrounded by overwhelming beauty, the calm was unnerving. As I watched the sun rise over a flat, glassy ocean, all I could see was a ticking time bomb. I didn't have a minute to spare to embrace the duality of the ocean’s cathartic dance between beauty and chaos. I knew the stillness wouldn't last. These moments of tranquility on the Atlantic are fleeting, and if I wanted to circumnavigate the entire coastline of Mi'kmaw'ki, I had to make the most of them.

Somedays, along the exposed areas of the Atlantic shore, the horizon line disappeared completely. All that remained in its place was a procession of giants. I watched these oncoming swell sets swiftly build until they stood right beside me, the largest of them three to four meters in height. Waves exploded off headlands and point breaks, vicious rip currents and hidden shoals produced turbulent swells that shot fountains of seafoam flying into the air. The only viable route was to paddle way offshore. There I was, paddling roughly one and a half kilometers away from the safety of the coastline with not another watercraft in sight when I entered a rhythmic state of flow. My paddle was dipping in and out of the water like a metronome, my mind and body working as one, with my awareness fully present in form – almost. I was paddling at the edge of my mental and physical capabilities, alone, in a dramatic and awe-inspiring environment, and I didn't even take time to embrace the experience.

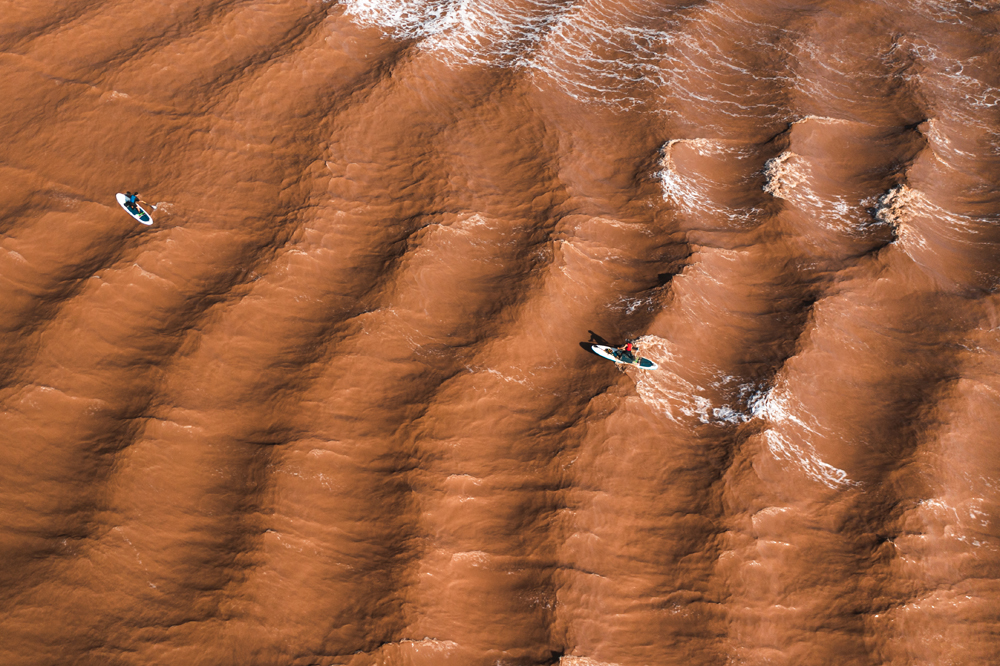

Five weeks into the expedition, after 23 days of paddling and with great humility, I completed the Atlantic coast leg of Nova Scotia. The next section was the mighty Northumberland Strait. Tucked in the shelter of Prince Edward Island, the calm waters of the Strait provided gentle paddling and time for reflection. After long days on my own on the water, my friend Dan joined me. The warmth of companionship, late-night driftwood fires on the red sand beaches, vulnerable conversations, and impromptu afternoon clam-digging overshadowed the constant desire I had to keep moving. I began to develop a deeper intuitive relationship with the environment that surrounded us. The clouds told stories about the trajectory of the day’s wind patterns, and the winds whispered warnings of impending changes in the sea state. When the Northumberland Strait came to an end, I hopped a car shuttle to the top of the Shubenacadie River where I prepared to enter one of the most intimidating sections of the route. Well-known for having some of the highest tidal fluctuations in the world, I was about to enter The Bay of Fundy. Playtime was over. This mighty crossing brought me back to business. It was time to finish my circumnavigation.

The Shubenacadie River is renowned for its tidal bore phenomenon, with 10 to 15 meter tidal range, and 10 to 20 kilometers per hour currents. Every day with the flowing tide, a wall of water rushes up the muddy, mineral-rich river leaving in its wake a series of tumultuous whitewater rapids and standing waves. The tidal currents are too strong to paddle, and the paddler is perpetually at the mercy of the tides, the cycle of the moon, and the position of the planet in the solar system. The red sandstone cliffs along The Bay of Fundy tell ancient stories about the earth's history and the many species that roamed the land long before we humans did. They are a constant reminder of the fleeting nature of our lives as individuals and of our existence as a species. Any feeling of desire or obligation, to circumnavigate the entire coastline was gone. The objective hazards in front of me which previously evoked anxiety and frustration now summoned waves of both awe and a deep sense of gratitude.

I surrendered to the ebbs and flows of this tide. With them, my objective-based ego and end-goal floated away on the outgoing waters. I spent seven days paddling the tidal bore at The Bay of Fundy. For twelve hours a day, I found myself surfing the flow upriver and riding the ebb downriver. In these moments of living according to the rhythms of nature, I released my attachment to my previous expectations, and made the conscious decision to let myself play to fully embrace the lessons of the ocean. This expedition was never about conquering this coastline; it was always about deepening my connection with it.

After three months, 1,213 kilometers of paddling and 31 kilometers of portaging, I completed my expedition. I may not have achieved my original goal of circumnavigating the entire mainland, but I got more out of this experience than I ever thought I would. The Mi'kmaw'ki coastline taught me how to view obstacles and see more than just the swirling images of my mind. Instead, I learned to surrender and see nature in its truest form: duality, chaos, but above all, immense beauty.