In April 2023, I stood on Paige Alms’s porch as she did something I’ve never seen before, and something I will likely never do. My friend stood on the very top of her 10-foot ladder, balancing her big feet on the narrow step, and reaching her arms up straight overhead. She was hanging a disco ball from the porch ceiling for her upcoming 35th birthday party later that evening.

To me, this was an impossible task. To her, it was just what needed to be done and she didn’t think twice about how hard it was. Was she scared atop that ladder? No. I reminded myself of the fact that in comparison to taking off on 50-foot waves at Pe’ahi, hanging a disco ball was a piece of cake. I also reminded myself that she’s superhuman and lives in a league of courage and skill where few others dare to walk on this watery planet.

That day, Paige was following through on a lifelong dream of throwing an amazing party at the home that she owns and helped to build. She has worked incredibly hard to make this dream a reality. Paige and her community of close Maui friends danced all night, the disco ball throwing shining, sparkling lights on her smiling face. It brought me so much joy to see my friend make her dreams come true.

When I think of big wave surfing, I think of Paige.

I first met Paige Alms at the US National Amateur Championships when we were both teenagers, just after Y2K. Since that time, I’ve literally and figuratively looked up to her tall 5'11" frame.

In her late teens, Paige’s shortboarding skills were top notch and she was a legitimate competitor; however, although she strove hard to compete on the World Championship Tour, no big-name sponsors funded her campaign. Paying her own travel expenses from her home on Maui to events all over the world to compete in the Qualifying Series of the World Surfing League proved both unaffordable and less than desirable. At that time, the women’s prize money in surfing was only a fraction of the men’s tour, and by the time 2007 came along, the epic barreling waves that Paige dreamed of surfing on the WSL World Tour were scratched from the women’s schedule (but not the men’s).

Paige decided to pivot her focus, even though her peers all knew that she had the full mixed bag of skills needed to compete with the world’s best on any tour. But Paige had bigger dreams in mind.

Paige Alms was lucky enough to grow up within miles of the legendary greatest wave in big wave surfing, Pe'ahi, otherwise known as Jaws. Her propensity for powerful waves naturally drew her to consider exploring the possibilities of paddle surfing the giant waves in her backyard. At the time, only one woman, Andrea Moller, had started paddling into Pe’ahi, but that was enough to pique Paige’s interest.

Paige has been in a relationship with Sean Ordonez, who is one of the top board shapers who paddle into and ride the world’s biggest waves, for many years. Sean comes from a windsurfing background and understands the dynamics of how board design moves with both water and wind. While many surfers generally stay away from windy conditions, this isn’t a possibility at Pe’ahi. Maui is known as a windy isle, and even the glassiest days at Pe’ahi have strong winds coming up the face of each wave. Most often, the trade winds blow in a side off-shore direction, which demands surfers navigate heart-stopping moments of airborne flight as they drop in from the lip into steep giants of moving water.

Paige quickly developed a high comfort level and technical ability at Pe’ahi. Applying her expert techniques from her shortboarding skills now allowed her to launch into intense take offs and carve bottom turns at maximum speeds.

In 2014, Paige rode what is - in my humble opinion - the best wave ever ridden by a female. On a massive set wave at Pe’ahi, Paige executed a perfectly-timed, long bottom turn, and then she drove back up the face of the wave, tucked in under its mighty lip, and double hand-dragged herself into a massive tube, exiting out into the channel with style and poise. I’ve watched the video of this wave hundreds of times. That moment encapsulates a feeling I may never know as a surfer, but it is one big wave riders are chasing every day. To this day, that particular wave remains one of the best paddle-in barrels to ever be ridden at Pe’ahi by either a man or a woman. It was the wave of a lifetime.

Paige went on to win two Big Wave World Titles at her home break in Pe’ahi, showcasing her uncanny ability to navigate the towering peaks, the powerful wind gusts, and clamp down on the nerves necessary to paddle over the edge of a detonating wave at Jaws and commit to dropping in.

Paige is an intellectual who never shies away from diligence. As big wave events began to pop up, Paige was an integral part of a group of women who bonded together to demand additional opportunities and equal pay for women in professional surf competitions. This core group succeeded when the WSL eventually honored and embraced equal pay in surfing, thus becoming the first North American sporting league to do so.

In Paige’s career as a big wave surfer, the scenery has changed. Little by little, there are now more opportunities opening for women. From the mid- 2010’s when supposedly women weren’t good enough to compete at the Mavericks Big Wave Invitational, to the current standing of having ten women included in the famed Eddie Aikau Invitational (surfing the same heats as the men), we could say we’ve come a long way. But, in reality, there’s still plenty of room for growth.

The Eddie Aikau Invitational is widely accepted as the pinnacle event in the world of big wave surfing. Last year in 2024, the women, for the second time in history, competed alongside the men without their own division. I asked Paige if she thought the mixed heats were a result of budget or the constraints of having to pay out two equal prize purses.

She laughed and said, “I think that probably has something to do with it, but it's kind of funny because if that's the reason, then they're looking at it the wrong way. I believe more money would be brought in if the men and women’s divisions were separated and if they put equal energy into both the men’s and the women’s competitions. I can't tell you how many people have asked me why The Eddie Aikau Invitational doesn’t crown a women's champ.”

She continued to say, “I'd love to have a heat with eight women out in the lineup together who are all going to actually send it. It's such a different vibe when there are only women in the lineup. You know when it's your turn, and you know who's going to go when they start paddling. When it's all women, you paddle back out and it’s a bit of a kinder circle. Like, okay, if I just caught a set, then now it's not my turn.”

I can only imagine how intense dropping into a maxing wave at Waimea might be. It is clear that when money and accolades like The Eddie Aikau Championship are on the line, the guys don’t back down from paddling in deeper and taking off deeper.

Paige continued, “I’d love the opportunity to actually send it on a set out there during the event. There’s this whole argument that ‘the girls don't even want the big ones’. I don't wanna share a 40-50 foot wave with someone who’s paddling in five feet deeper than me. And in talking with the women, we all want that opportunity to surf the heat together. All of us think it would be much more valuable and we’d have the opportunity to showcase our skills even more.”

Paige reflected that she’s hopeful the decision makers for The Eddie will continue to see the benefit of highlighting the women and offering them their own division without the female athletes having to fight for it as they have done in the past.

Big wave surfing is a sport not for the faint of heart, nor for those fearful of getting injured. Everyone who participates has to accept that there are intense wipeouts and treacherous scenarios that involve the body being tossed in violent white water under enormous pressure.

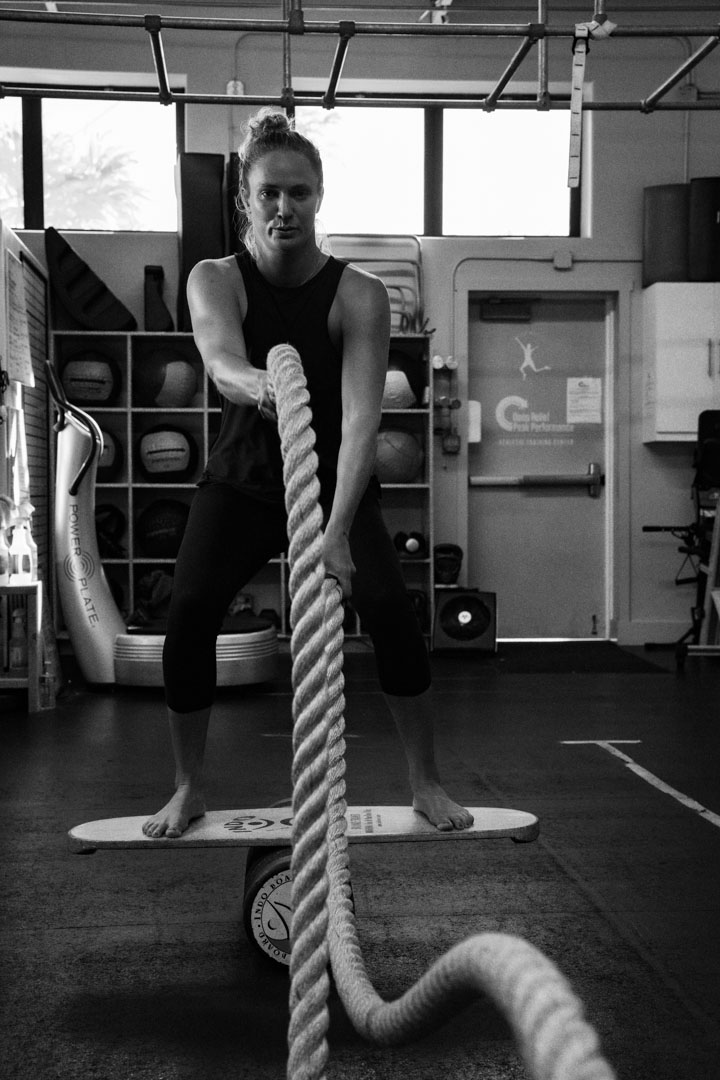

I asked Paige if she thinks training is necessary to be a big wave surfer. She responded, “Yes, for sure I think it is necessary! I think some people have natural talent, especially the younger groms who are already so fit and surfing so much that training isn’t at the forefront of their minds. It's not until they hit their mid-20s and actually start experiencing really serious injuries that training becomes part of most athletes' routines. Once you're in your thirties, you need to be prepared for that eventuality. Your body changes — it's just different.”

She continued, “The stronger you are, the faster you can paddle. Also, the more fit I am, the stronger my mind becomes. I truly feel the best when I'm feeling really fit. When you get pounded, knowing that your body has been trained for that moment and is ready for it makes a difference too.”

“I feel that when you're at peak physical strength that’s important for sure, but the positioning and the actual will to send it at the critical moment when you’ve just gotta turn and go, that's all in your mind. There's a point where it becomes a mental thing. You need the strength in your legs to make the bottom turn, but you won't get to that point where you're making a bottom turn unless you have the mental fortitude to get over the ledge.”

For over a decade, Paige has been adamant about training hard in the gym year-round, keeping her body in prime shape so that when it comes down to the mind game, her body is prepared.

With acute attention to detail, Paige is interactive with her surfing equipment. After all, trust in one’s board is paramount for having the confidence to drop into a wave at Pe’ahi and successfully ride it out at top speed. She explained her testing process to me, “We make minor little changes to boards that we've tweaked in prior years. Sometimes we tweak stuff and then end up going back to something we used before that works better than a new modification. Right now, my boards are feeling really good, and I know them really well, so I'm just kind of playing with different fins.”

“I still find myself trying new things, but sometimes, I like to just use what has been working for me. I only ride a certain number of waves per session. I'm not Kai Lenny, catching dozens of waves every session. I go out with the intention of finding one really good one. It's only been a handful of times that I’ve ridden more than three big waves in a session. I'm not going to take off on any wave just to ride waves and I guess you need to do that in order to be able to test a lot of equipment. I'm a firm believer that I can paddle out on a 5-6 foot day at Ho’okipa and notice the difference in my fins or board. I'm probably not pushing them to their limit as it's not the same feeling as riding a 10 to 20 foot wave because you're going at such different speeds then. But I can feel whether I could pivot quicker, where I could dial in the acceleration or the speed control."

Paige, as the courageous waterwoman she is, has explored the various forms of foiling. From riding waves, to winging, to downwind paddle foiling, she utilizes this hobby as a cross-training tool during the summer. Paige describes the design of foils as being inspired by pelicans and their wing shapes that enable lift. When asked if foiling and big wave surfing complement one another, she responded, “Definitely. With foiling, you can ride at the speeds that you find on big waves while on a tiny wave or even waves that aren't really breaking. Foiling is good training in the sense of experiencing speed and how to control it.

“Riding a 20 footer versus a head high wave, you're going at such different speeds. So with foiling, you have exposure at similar speed for longer periods so that you can get used to it. The only thing is that your stance on a foil board is different. Some people have a wider stance but for me, with foiling, my stance is a lot narrower. For power and efficiency, a rider wants to be standing over the foil, so you have to narrow your stance.” She laughed. “In that respect, I try not to foil before I'm gonna surf big waves.”

“Harnessing and understanding speed while foiling has totally changed the way I look at the ocean and the way I understand how it moves. I feel like I can see things differently because I’m looking for a different kind of bump in the water, and I’m able to recognize the way that those bumps are developing earlier. I've learned to utilize this knowledge to my advantage in big waves. I feel that similar knowledge comes also from surfing in the wind here on Maui because some of our smaller waves do very similar things at Jaws in the sense of where the power shifts with the wind on the wave. It may not be the picture perfect, top-to-bottom A-frame that you're used to seeing from the cliff. It’s actually far from that. Those little intricacies of knowing where to be on the wave and what that little wind chop is gonna do comes from just surfing in the wind. People who don't surf in those conditions, don't see the nuances as easily.”

So I asked, “How did you become friends with the wind?”

She laughed, “Living on Maui, you'd be really grumpy if you didn’t become friends with the wind. You just have to embrace the wind as a part of surfing and learn how to utilize it instead of letting it hinder you. We'll have weeks on end here where it's just howling and stormy. That’s just part of living on an island.”