I’m an improbable foiler. I grew up on the prairies of Canada, in Saskatchewan. I skateboarded during the short summers and spent lots of time figure skating on the ice during the long winters. It’s a cold place. During my last winter, there were 30 days when the temperature fell below -30C (-22F). I studied engineering and went on to graduate school in Mechanical Engineering at MIT. I met my wife, Sheila while at MIT, and we moved to upstate New York 15 years ago.

Perhaps watersports were in my blood, but I didn’t discover this until my late thirties. I’ve surfed small ocean waves, but only on vacation, and I still haven’t foiled in the ocean. I don’t know how to kite board, and have only used a SUP while on vacation. Three year ago, I saw a foil on the lake and assumed it was yet another toy for the water. I wanted to try it. I found I had a lot to learn!

Why foil? There are two strong reasons. The first is the experience of human-powered flight above the water. My personal jaw dropping moment that transformed an interest into a passion was seeing a hydrofoil “pumped” on the water. The up and down motion we call pumping on a foil is to propel it forward, unassisted. This seemed impossible to me. I studied fluid mechanics and aerodynamics, but without understanding flapping flight it’s hard to understand how a foil can be propelled by “pumping.” I had to figure it out.

The second reason for learning to foil is in order to experience surfing an endless wave on a lake. How do you surf a wave on a lake? For those frequenting calm lakes, the only endless wave we will ever find will be created by connecting the wakes of passing boats. It’s thrilling. And to do it we need to pump long distances, and we must regain our energy while surfing a wake before finding the next wake to pump to and ride. We call this wake thieving.

My best friend and neighbor Justin experienced the feeling of flight atop the Lift eFoil while on vacation in Puerto Rico. He was hooked too. Justin is a technology teacher, and has an immense capability to visualize and build nearly anything that hasn’t yet been built. A year ago we scoured YouTube and watched nearly every video we could find on foiling. There wasn’t much out there about lake foiling. For that reason we decided to start a YouTube channel, and called it Wake Thief.

We didn’t know much about foiling and we knew nothing about YouTube. Sounds like a great plan, right? We pushed forward anyway, eager to share what we learned, and we’re so glad we did. Great ideas started flowing in, we made new friends, and we learned much more than we expected.

We have yet to find someone who didn’t like the sensation of flying on a foil. Our goal is to bring that joy to others, and help them learn to fly. There are many foils to choose from, maybe too many. At our last count, there’s 57 brands, and choosing a foil that’s right for you can be overwhelming, particularly when someone is trying to build their first foil from the six main components that comprise a foil (board, base plate, mast, fuselage, rear wing, and front wing). It creates almost endless possibilities. Some manufacturers have so many options you can create >10,000 unique foils from the components they sell.

Once Justin and I tried many foils, we realized they’re more alike than different, and you can isolate their differences fairly quickly if you qualitatively test each foil, show their performance back-to-back with another foil, and determine the cause and effect. We made this the most important principle of our reviews on YouTube. We want to feel the difference, demonstrate the difference, and show viewers how the foils perform so they can see it with their own eyes. When we took this approach, we started to uncover differentiation, and more importantly, we could explain it.

While Justin is a mechanical genius and I’m an engineer, we needed to enlist the help of experts to understand what we were learning. With the added help of some new friends, we dusted off several old textbooks, turned my lake front into a test facility, and transformed my basement into a chop shop. My 2017 Yamaha WaveRunner became the wake maker, so we could create repeatable wakes for us to surf-test each foil. We set up a bungee to launch from my dock into a 30m course in order to measure pumping speed, gliding distance, takeoff speed, and pumping duration for different foils. We covered my property in GoPro camera mounts, and let the cameras roll, documenting our journey to find the perfect foils for the lake.

On this journey, the most common question we receive is: How do I choose the right foil?

Most of the 57 brands have multiple rear wings, front wings, mast lengths, mast thicknesses, and fuselage lengths to choose from. This allows a foiler to create many unique foils, even within a single brand. On the one hand, this gives nearly endless possibilities. On the other hand, it can be overwhelming for those wanting to enter the sport. We receive many comments from “soon-to-be-foilers” ready to throw their hands in the air and give up before their first flight. The idea of flying around the lake on a foil is attractive until you realize your ~$2,500 investment decision is not going to be an easy one, and no one wants to make a mistake. I, myself, purchased three foils before figuring out what I liked to do, and then what I needed in order to do it well. We are trying to help “soon-to-be” foilers enter this great sport as painlessly as possible.

Over the course of the last year Justin and I tried more than 30 foils. We learned about each of the components selection and how they change the performance of each foil. This helped us arrive at the attributes of a “go-to” foil for wake thieving.

We learned that the front wing is the 800lb gorilla. It matters most. The good news is that if you get this right your foil will probably be good. We also discovered that larger area, high wingspan wings are the ticket towards endless flight. Very large front wings (>2200sqcm) fly at a slow speed, which is great because you can exert less power to pump if your speed is lower. However, these big wings tend to be thick for strength and have high drag because of their larger area, so a foiler can’t glide as far between pumps, which makes pumping more tiring. If the front wing is too small (<1200sqcm), it requires a very high speed to fly and thus you need to pump it at a high rate of speed to create enough lift; therefore, you tire faster. So the perfect wing has a large enough area and low enough drag. As it turns out, few wings have both a large area and low drag. The aspect ratio is determined by the span, divided by the average chord. High aspect ratio wings look like gliders, with a very large wingspan. Why does a glider have lower drag? It’s because the tips are where high pressure below the wing meets lower pressure above the wing, and high aspect ratio wings have a smaller area at the wingtips, a smaller percentage of the overall wing area. So we wanted large glider wings, and they are few and far between.

In the summer of 2020 we discovered the AXIS 1150 PNG. This was the largest area, highest aspect ratio we could find. And it’s our current favorite for the lake. It’s 1778sqcm area, combined with 115cm wing span and aspect ratio of >7. It has transformed my pumping distance, allowing me to reach 2.5 minutes, a feat I’ve been unable to achieve with any other foil. This relatively large area and high aspect ratio is both unique and rare. I looked long and hard to find the contact information for as many of the 57 brands I could find. We’ve contacted nearly every brand in search of their biggest, highest aspect ratio wings, as we believe this is what we need to fly longer.

The remaining component selections matter, but a lot less than the front wing. Thus, we tend to like the “middle of the range” sizes of most brands for these remaining choices. Not the largest or smallest of any mast, rear wing or fuselage, but something in between.

The mast connects the board of the foil to the glider section. We want a mast long enough to fly above passing wakes, yet short enough to maintain control of the foil. A thicker, stiffer mast is key to ensure high power transfer while pumping. We believe that we’ve seen few >115cm span front wings on the market because the mast of many brands just isn’t stiff enough for wings of this large a wingspan.

The fuselage connects the front wing to the rear wing, and changes the pitch sensitivity of the foil. We prefer a fuselage that measures 70-80cm from the leading edge of the front wing to the trailing edge of the rear wing. Each manufacturer has different fuselage lengths, but this tends to be a “middle of the road” selection. We can pump longer with longer fuselages, as the thrust generated by the rear wing is higher, but if the fuselage is too long, carving is compromised. Again, a “middle of the range” selection tends to win out.

The rear wing helps control pitch and provides thrust during pumping. We prefer thin rear wings, with relatively large area, and high aspect ratio. This will provide better thrust during pumping and low drag while flying, which helps reduce the overall pumping power needed.

For “wake thieving”, all of these choices paired with a shorter (<3’6” ft / <107cm), low volume board (<15L), require less power while pumping the foil because the shorter, lighter boards experience less inertia (“swing weight”) while pumping, as compared to larger boards. Mass far from the pivot point (close to where the mast connects to the board) creates a lot of inertia that needs to be overcome each time the direction of board motion changes.

It took us a year of trying many foils before we arrived at a rating and scoring system that we believe can be used to compare the performance of different foils. In the spring of 2021, we asked viewers to share the foils they’d like us to review, and our list has grown to more than 15 new foils. It made sense for us to set the standard, a benchmark, with our favorite foil for the lake, the AXIS 1150 PNG. If you have any foils you’d like us to review, please let us know. And if you’d like help finding a foil, please feel free to email us at wakethief@icloud.com with your weight, boardsports skill level, and how you want to use the foil.

We discovered that three things are necessary for long-distance flight on a foil: (1) The right foil, (2) The right technique and (3) The right fitness. With the right foil, and our fitness improving each day of practicing, we needed to focus on #2, the right technique. Without any text books describing how to flap a foil like a bird flaps its wings during flight, we needed to dig into the physics of flapping flight to figure out how we might fly forever

How to Pump … Forever?

The key to endless flight on a foil will be understanding how a foil works … how it really works. One of the unexpected surprises of YouTube is the quick network one can establish of similarly interested people from around the planet. I had the pleasure of meeting Todd Reichert and Eirik Bochmann. Eirik is based in Norway, and is the CEO of a company called Wave Foil, a company that produces foils for large vessels. He’s a foiler with a PhD in Hydrodynamics and has given me a ton of guidance on my journey to learn the physics of flight with a foil. Todd is not only a flapping flight expert & aerodynamics PhD, he is a celebrity in the human-powered flight community. Todd & his team have a human-powered land speed record at 89.59mph. He also developed an airplane with flapping wings, and he’s pedaled his way into the air as a human flier.

During our first meeting it was like we had known one another for years. I suppose that’s what happens when the passionate share their passion with each other. In our very first meeting, Todd showed me that we might be able to pump for a very long time, because if the human body can do something for 2min, and can reduce the power to do that activity by just 25%, the power demand reaches a level that we can sustain for much longer. Last summer I pumped the AXIS 1150 PNG hydrofoil for 2.5 minutes, which as a healthy male, we can assume means that I was exerting roughly 340W to do that. If we could figure out how to reduce the power by 25% to about 260W, this NASA curve for “healthy man” suggests I could pump for 30min. If I could pump for 30 minutes that would be 5.6 miles or 9km of flight!

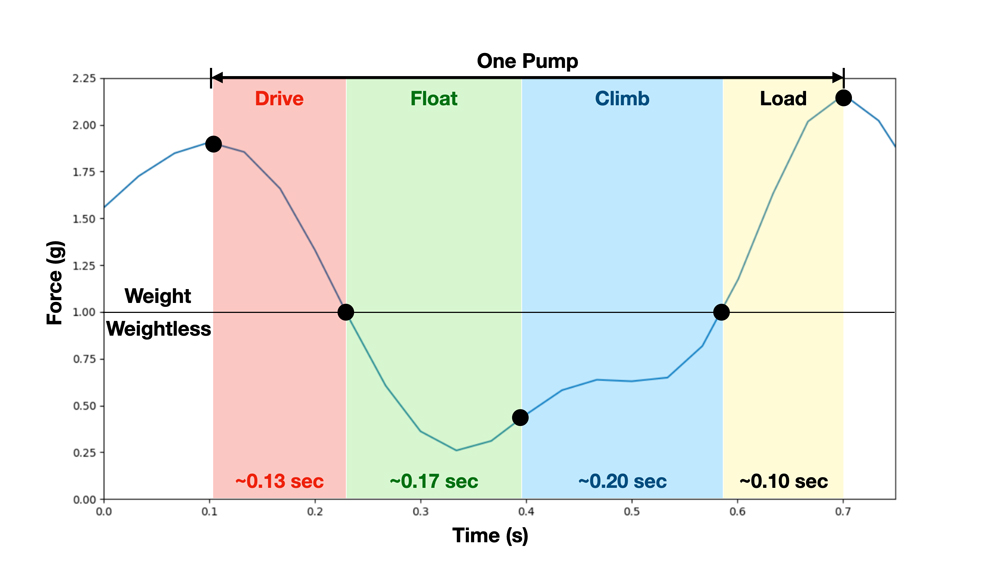

Our bodies have a way of adapting to accomplish a task efficiently, so it’s likely that many hours of pumping the same foil results in a certain technique that is likely close to optimal. We wanted to start with that, so Todd developed a kinematic model to help break down forces at each point while pumping a foil. Learning to pump takes time, so we wanted to shortcut the learning as much as possible. Having adequate force at each moment during the pump really helped me solidify what I was doing, so that I could better communicate to those learning to pump or seeking to pump longer and farther.

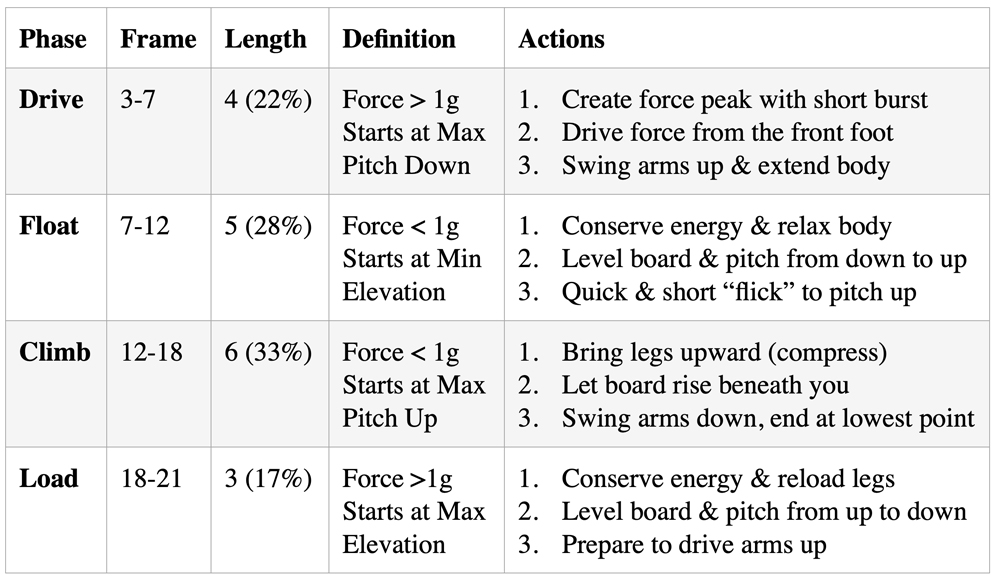

We thought of breaking pumping into four distinct phases: Drive, Float, Climb, and Load. These four phases are determined by specific changes in the pumping action, and all four happen very fast, in less than one second.

The drive is when we apply a sudden, short force to the board. It’s front foot-dominant to keep the nose of the board pitched down, and the force applied is a function of the speed you’re traveling. Sometimes you apply more force to go faster or less force to go slower. Remember you want to travel at that ideal speed. Any faster and your power demand increases. Any slower and you reach higher levels of drag as you approach the stall speed. In this phase, the force reaches nearly 2x my body weight for a short period. I tend to breathe out during the drive. Note that because the nose is pitched down, the lift force on the front wing (which points upward as the wing lifts to overcome your body weight) is also pointing a little bit forward.This generates thrust! I didn’t realize that until we completed this analysis.

The next phase is the float phase. The float phase begins with the mast at its lowest point, and the board closest to the water. This phase also begins once we’re at 1G, and that's when we go weightless. In this phase, we conserve energy and relax our bodies. We level the board out and sweep from pitch down to pitch up in a swift, flicking action with our back foot. The entire time, we are less than 1G. We’re somewhat weightless. This phase ends with your reached maximum pitch up with the board.

At max pitch angle the climb phase begins. As a skateboarder, this feels like an ollie. By the end arms are at minimum height and you accept the force of the board with your back foot. There’s a point where there’s very little force on your back foot, it’s barely touching the board, and it is more to keep the board under your feet so it doesn’t fly away. Because the nose is pitched up, the lift force on the front wing will be pointing up (as expected), but also a little bit back, so this actually slows you down. Therefore, in this phase you’re better to be light and as weightless as possible, so that the portion of the lift force pointing backwards isn’t that big. In this phase, I don’t want to say jump, but go weightless, almost lifting your knees upward and letting the board rise beneath you, due to the lift force being created by the wing. I tend to take a breath in during the climb.

The final phase is called the Load phase. It begins at max elevation, with the board furthest from the water. In this phase you conserve energy and reload your legs after weightlessness. It feels like landing on the board. You level the board and sweep from pitch up to down. You prepare your arms to swing through, like readying to jump, but don’t begin the drive until the nose is pitched down.

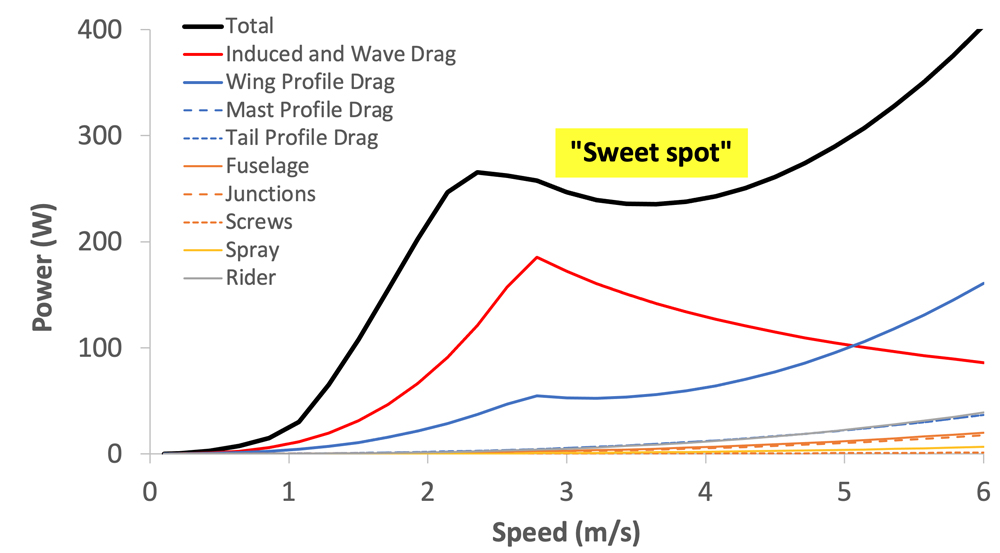

Beyond just how to pump, and breaking down the mechanics of pumping, Justin and I want to understand where the power is being consumed during pumping. Todd created a physics-based model that simulated our “go-to” foil setup, considering nearly all of the possible sources of drag, even the spray off the mast while pumping. What’s most interesting is the local minimum found in the power needed to pump a foil. When the speed is too low, the wing generates more drag due to high angles of attack, which steals energy. But if you speed up too much you’re consuming power just to fly at a higher speed. That’s why there’s an optimum pumping speed for each rider and each wing. Our bodies have a way of finding it through trial and error, and finding it is key to unlocking endless flight on a foil. For me, the “sweet spot” for long distance pumping is about 3.5-4m/s (12.6 - 14.4 km/hr, 7.8 - 9.0 mph). Not too fast, not too slow …. just right.

Long distance pumping is about fitness, but it’s also about the right technique and the right equipment. We believe these latter two things are critical to unlocking endless flight on a foil. We feel like our journey is just beginning. It took us a long time to determine our favorite foil, and it took us a while longer to figure out what we need to fly forever on our foils.

It was only a year ago we started sharing our experience on YouTube, and we still have so much to learn. The excitement of flight is contagious, and we see it in the smiles of everyone who flies. Even at 200+ hours of flight time, I’m still smiling. I’ll be working, reviewing footage for an upcoming video and will catch myself smiling. I hope that never changes. When I’m foiling I still look at that wing under the water with amazement, wondering how it can let me fly.

Last week, I took my 7 year old for his first flight. He’s flying on his stomach, dragging his legs behind him to steer the foil. Every day he asks me if we can go out and foil, and it’s about the easiest thing to say yes to. We might have a Little Thief in the making.

@Wakethief on YouTube, Facebook, TikTok, Instagram