How long can you hold your breath? This is a particularly common question when talking about big waves that could potentially result in long breath hold times. The duress of being underwater is enough to scare most people from ever stepping off the beach. Toss in the elements of tide, current, surf and depth and you'll likely turn away those that were on the fence about dipping a toe. Most of us are never as comfortable underwater as we were at birth. In fact, infants are remarkably at ease below the surface due to a primitive reflex that instinctively makes them hold their breath when immersed in water. As we get older, our emotional anxieties and physical limitations create self doubt in our ability to relax when we're below the surface, resulting in shorter breath holds and a natural inhibition towards open water.

The average adult can hold their breath for 30 to 90 seconds depending on factors like lung health, medical conditions, and training. On average, we take a breath about 12 times per minute. A common misconception when practicing a long breath hold is that the gasp for air at the end is caused by a deficiency of oxygen in our body. That may be the case in some circumstances, but more than likely that gasp is triggered by a build up of CO2 gas. The medical term is called hypercapnia which is a build up of carbon dioxide in your bloodstream. The cells in our bodies are constantly processing nutrients to create energy, which in turn generates CO2, which is then carried by our blood to the lungs to be exhaled. When you're holding your breath for long periods of time, those CO2 levels become critical enough that they trigger the diaphragm to force an exhale by convulsing.

Convulsions generally start around the 2:00 mark of a breath hold and are generally convincing enough to force you to the surface for a reset. However, if you're purposely pushing your breath holds because the surface is unreachable, or you're purposely training your tolerance levels, this is when the hard work begins. CO2 tolerance training is a regular routine practiced by most water sport athletes. By increasing your CO2 tolerance, you can push the limits of your breath hold capacity, which obviously translates to increased confidence and capability in more extreme situations. Staying relaxed in critical underwater situations is the secret to longer hold times. It's easy to start panicking when you feel like you're running out of air, but that anxiety only elevates your heart rate which in turn puts more pressure on your oxygen reserves and greatly diminishes the time you have before you need to breathe.

Fortunately, there is a natural instinct we all possess that helps to extend our time underwater with little or no training. It's called the mammalian dive reflex. This reflex kicks in the moment you put your head in the water. Once your face and nose become wet, a state of bradycardia is initiated which is a slowing of the heart rate to limit unnecessary oxygen consumption. A typical person's resting heart rate will drop from 80 to 50 beats per minute and the blood that was flowing to your extremities will be redirected to the two most critical life-saving functions - your heart and brain. Many of the top water athletes push the limits on oxygen deprivation by holding their breath up to and beyond the point of unconsciousness. Black outs can commonly occur when the brain is starved of oxygen long enough to induce high levels of cerebral hypoxia. The hypoxia and general detached mental state that comes with it creates a feeling of euphoria that can falsely empower us to continue to hold our breath to the point of unconsciousness. After four to six minutes of oxygen deprivation, irreversible brain damage is the next stop on the line.

I personally participated in a breath hold workshop a few years ago hosted by Joe Sheridan and Alex Lllinasof Waterman Survival in Puerto Rico. The duo run multi-day workshops focused on breath hold training through pool and open water drills and skills. The first of many exercises we practiced was a simple static apnea test designed to measure breath hold times with zero movement. In this exercise we stood in the shallow end of the pool and began "breathing up" by performing long slow inhales and exhales to exercise our lungs, calm our heart rates, and discharge as much CO2 as possible. Once the ten breaths were completed, we simply dipped our faces into the water with our hand on the edge of the pool for security and our partner at our side for safety. "Go to your happy place" were the words I heard from the slow drawling North Carolina native who sounds and carries himself more chill than the Buddha himself. It was easy to relax when I focused on Joe's voice until the moment the convulsions started. There's nothing more harrowing than experiencing involuntary diaphragm spasms while holding your breath underwater. Each convulsion echos the signature of the imminent drowning to follow unless immediate contrarian action occurs swiftly. "Stay with it, work through the uncomfortableness," says Joe. I was much more than uncomfortable, I was one step shy of full on panic mode. As I stood up in a violent jerk-like reaction my mouth opened wide and I took in a huge breath of air feeling very proud to have put my oxygen deprivation limits to the test.

"You know you still had plenty of oxygen when you came up, right?" The man who seemed so confident that I could have stayed under even longer was standing at the edge of the pool crouched down in front of me. "I don't know man, I was convulsing like crazy. I needed to take a breath badly, " I explained. "Yeah, but your lips and cheeks are still pink. If you were really in need of oxygen, those pink areas would be a light shade of blue by now." That was my first lesson in CO2 tolerance and the first time I met Alex Llinas.

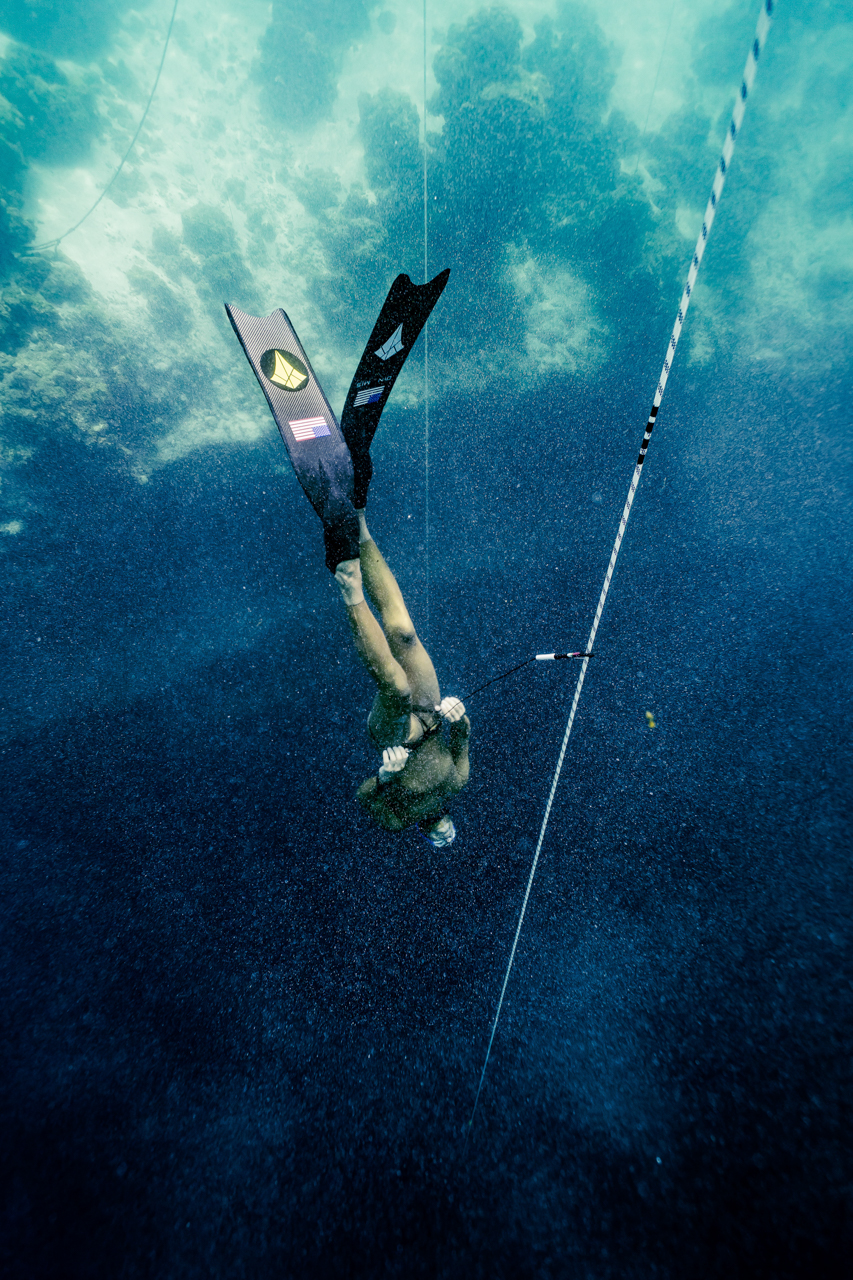

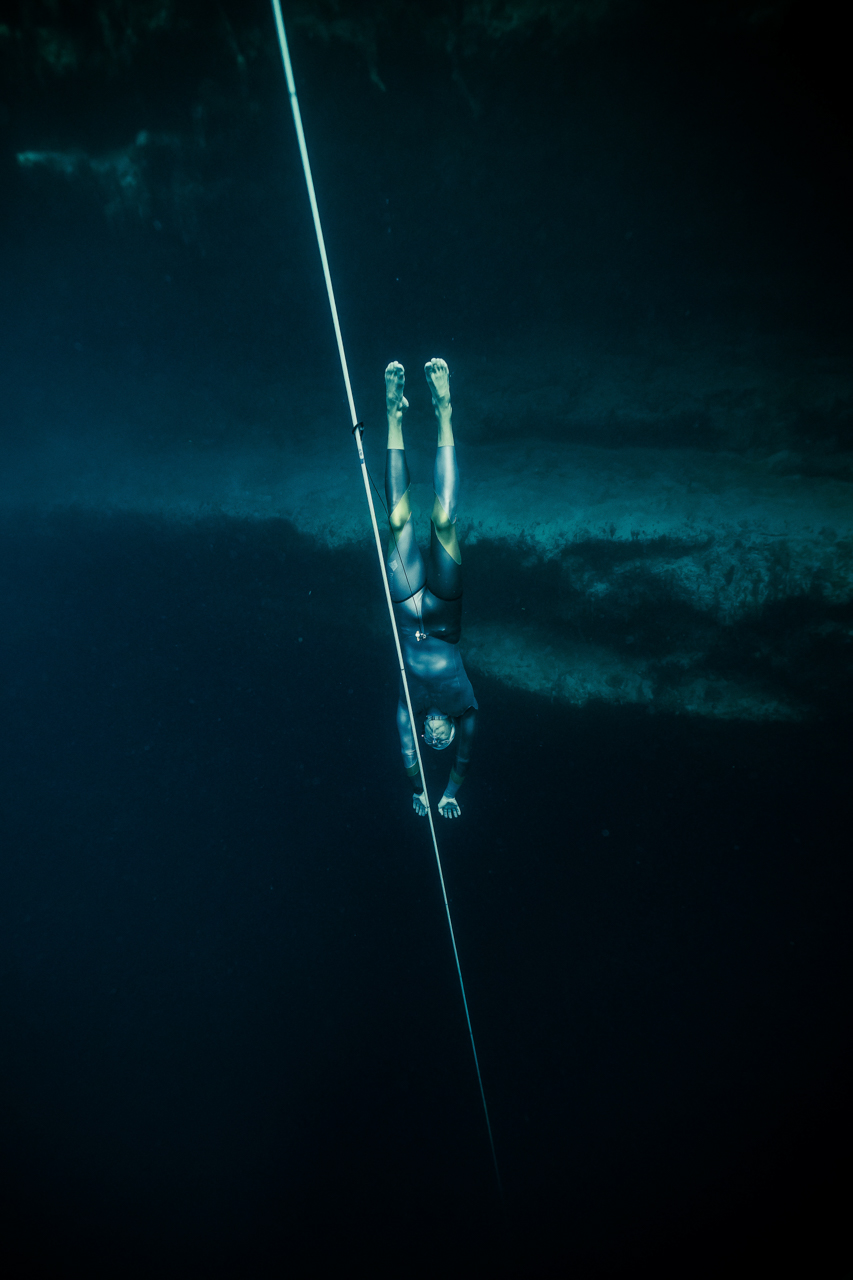

Alex is a national and continental record holding freediver from Colombia. No sport on earth pushes the limits of breath hold more than freediving. In fact, freediving is so dangerous, it claims more lives than any other sport each year. The term freediving comes from the Greek word apnea which means “without air.” The sport is elegant in its simplicity - no tank, no snorkel, and in some cases, no fins. The goal is to hold your breath as long as you can while you descend to a depth or swim laps in a pool on a single breath. Divers compete using little to no equipment. The use of fins (or no fins) and the type of fins define the different classes of competition. Bi-fins are what we mostly commonly think of when we think of divers. These are long carbon fiber "blades" worn on each foot. Monofins are a single dolphin-tail-shaped fin where both feet and legs work together in a porpoise-like kicking motion to move the diver through the water. The best free divers in the world follow a competition circuit that takes them around the globe pushing one another to personal, national, continental, and world record setting bests. The locations for many of these events are held in beautiful geological phenomena like the one going on right now at Dean's Blue Hole on Long Island, Bahamas.

Dean's Blue Hole is the second deepest blue water cavern in the world at 202 meters, and is the host site of Vertical Blue, a freediving depth competition that Alex is competing in as we speak. In fact he just completed a perfect no fins dive to 70 meters following a low oxygen LMC or “loss of motor control” ruling the day before. Alex is an incredibly fit athlete who has competed competitively in triathlons, adventure races, open water swimming, indoor swimming, windsurfing, freediving and more. His unique talent is in his ability to persevere despite the overwhelming amount of tragedy and trauma he's had to face throughout his life.

Alex was born in Barranquilla, Colombia in 1978. His parents separated two years later in a traumatic separation that placed Alex in his grandmother's care until things settled down at home. He attended 10 different schools moving throughout the country between his father, uncle and grandmother's houses before the age of 16. In 1993 he needed permission from his mother, according to Colombia law, to leave the country as a minor. Alex's mother at the time was in a long drawn out battle with drug addiction, living on the streets without the mental capacity to grant him his travel visa. Following their only other course of action, Alex and his uncle had to pursue a legal route declaring Alex's mother to be legally insane and unfit as a mother in order for Alex to leave the country.

One month after his 16th birthday, Alex obtained his visa and entered the US with the intention of staying indefinitely. Three years later he was crossing the border into Canada for a high school graduation trip when he was flagged for having overstayed his visa and was charged on the spot with a false claim to citizenship. He spent one month in an immigration prison before being released on parole. He then spent the next 2.5 years traveling back and forth from North Carolina to New Jersey and New York for court date appearances to obtain political asylum in the US. Once finally granted in 1997, Alex was no longer able to return to Colombia or travel outside the US without a permit. In 2000 he moved to Raleigh and enrolled at North Carolina State University to pursue a degree in mechanical engineering. Two years into his college track, his father who had moved to Wilmington in '93 to start 'Mundo Latino' - a Spanish-speaking newspaper - was arrested by immigration officers and deported back to Colombia. Alex spent a good chunk of his senior year at NCSU trying clear his father's record and restore his business.

Alex spent the next ten years working for a mechanical engineering consulting firm. In 2012 he was informed that a car had purposely killed his mother in a hit and run accident. The driver was never found. In December of 2017 Alex noticed swollen lymph nodes in his inguinal area. He spent the majority of his savings on scans, tests and doctor visits before receiving his non Hodgkin’s follicular lymphoma diagnosis. Alex had cancer and would start treatment immediately following the Vertical Blue freediving event that he was running safety for that year. Just after the closing of that event, Alex recorded his first constant no fins (CNF) personal best at a depth of 58 meters. He would spend the next six months undergoing chemotherapy before getting a clean scan and being cleared by his doctor to dive again.

Alex was the interim chief of safety at the Roatán World championships in July of 2019 when he acquired a skin infection that he was defenseless against due to heavy doses of chemo. He was air evacuated to a hospital in Fort Lauderdale where he came close to dying from septic shock. He would spend another two weeks in that hospital where he was placed under neutropenic precautions to monitor his risk against future infections. Three months later he went to Curacao to compete in the Ocean Quest competition where he placed 2nd in CNF and set two national depth records. Alex was finding his groove and slowly making the transition from running safety to becoming a competitive competitor as a freediver. His progress up until that point was put on hold when the world went quiet during the years of the pandemic. Then on April 23, 2020 Alex's father, Alejandro Llinas Sr was murdered.

Alejandro Llinas raised his son Alex to be a waterman. "Since I can remember, I was always in the water. So my dad trusted my ability to take care of myself and not get in too much trouble," says Llinas. They spent a big part of Alex's early childhood on the small island of San Andres, Colombia where they both pursued a passion for windsurfing. Alex credits his father for the inspiration and support that fuels his passion for the ocean. "My dad was a competitive swimmer and triathlete and taught me to swim, dive, and windsurf at a very young age." Alejandro was an environmental activist committed to protecting protected areas of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region of Colombia. He had alerted the authorities multiple times of criminal activities taking place in the area, which ultimately cost him his life. "It’s hard to quantify what his loss in my life meant to me. All of my dives are dedicated to him," says Llinas.

From May 2021 through the end of that year, Alex was on the set of "Black Panther: Wakanda Forever" training the two leads, Alex Livinalli and Tenoch Huerta on how to get comfortable in the water. Alex had worked previously with the movie's director of photography, Pete Zuccarini, who was a freediver himself and a close friend. Alex's experience as a trainer served him well on the set as he was responsible for handling actors with varying levels of experience in the water. As an athlete himself he was able to double as trainer and stuntman in a lot of scenes. His lung capacity made him ideal for long shoots that required him to get into position before the cameras started rolling, handle and manage the actors through the shot, then get back to the surface on that one single breath. He had discovered a way to continue his training while earning a little money to finance his first year campaign as a competitive diver.

In August of last year Alex returned to Roatán, Honduras to compete in the AIDA World Championships. He finished that event with 4 national records, 2 continental records, one bronze medal, one silver medal, 2nd overalls and 4 personal bests with white cards. He finished the year ranked in the top 5 among AIDA divers and top 15 in all disciplines. I got a chance to catch up with him back in Puerto Rico last winter where he shared this entire story with me. I sat back bewildered by the amount of anguish this guy had experienced over his life thus far, but was in absolute awe of everything he had accomplished.

After two hours of sitting, he and I were both ready to move our bodies and get back into the water. There was a decent swell running that day and Tres Palmas was starting to fill in. We walked down the beach recounting some of the details from his life story before making the long paddle out to the line up. I sat on the inside and watched Alex take off on at least 10 waves that afternoon, each one bigger than the one before. He was high lining on a 10' longboard smiling ear to ear as he slid past me. I couldn't help but wonder how this guy had been able to keep pushing himself through all the shit he's experienced in his life? The smile on his face gave away his secret. Alex thrives in the ocean. It's his place of healing and serenity. There's nothing more still, more quiet, or more peaceful than immersing yourself in the tranquility and natural beauty of the ocean. For freedivers like Alex, this is their happy place. The place that provides temporary relief from the terrestrial stress brought on by time spent out of the water. Diving down to unfathomable depths with compounding amounts of pressure exerted on your body over incredulous amounts of minutes is one hell of a way to escape one's problems. I imagine you'd have to be running from a ton of stress and trauma if that feels like your happy place.

To follow along with the rest of Alex's competitive year or to simply reach out to send some love and support, you can reach him on Instagram @alex_llinas_freediver or by email at alex@in-sea.com.