In the lower latitudes of the South Pacific, the dawn air feels dense and slumbering. As the sun rises, light rain settles on the crested hills of this verdant island. Already men, and one particular woman, arrive sleepily at the marina.

First, the percussion ensemble: A cacophony of closing car doors signals the arrival of the day’s crew. Cans of Japanese green tea and black coffee are passed hand over hand and thumped down, one by one, into salt-stained buckets.

Next, the strings: the cascading sound of sliding zippers and muffled grunts fills the air as dry bodies wrestle into damp wetsuits. Newly waterproofed, and with buckets in tow, the crew hurries toward their waiting boats.

Finally, the horns: marine engines turn over. The metallic drone of compressed diesel muffles all other sounds as boats launch into Kumejima’s cerulean reefs. Eating greedily at the harbor’s lopping waves, the skiffs speed toward the seaweed fields.

The mozuku harvest begins.

I am riding along with Arisa Izeki, the only female seaweed harvester on this crew and the first female scuba instructor in Kumejima. Originally from Tokyo, Arisa has lived on this small island for decades. However, as I would come to learn, it took her several years to gain entry into the seaweed harvesting cooperative, due in no small part to the gender biases she encountered.

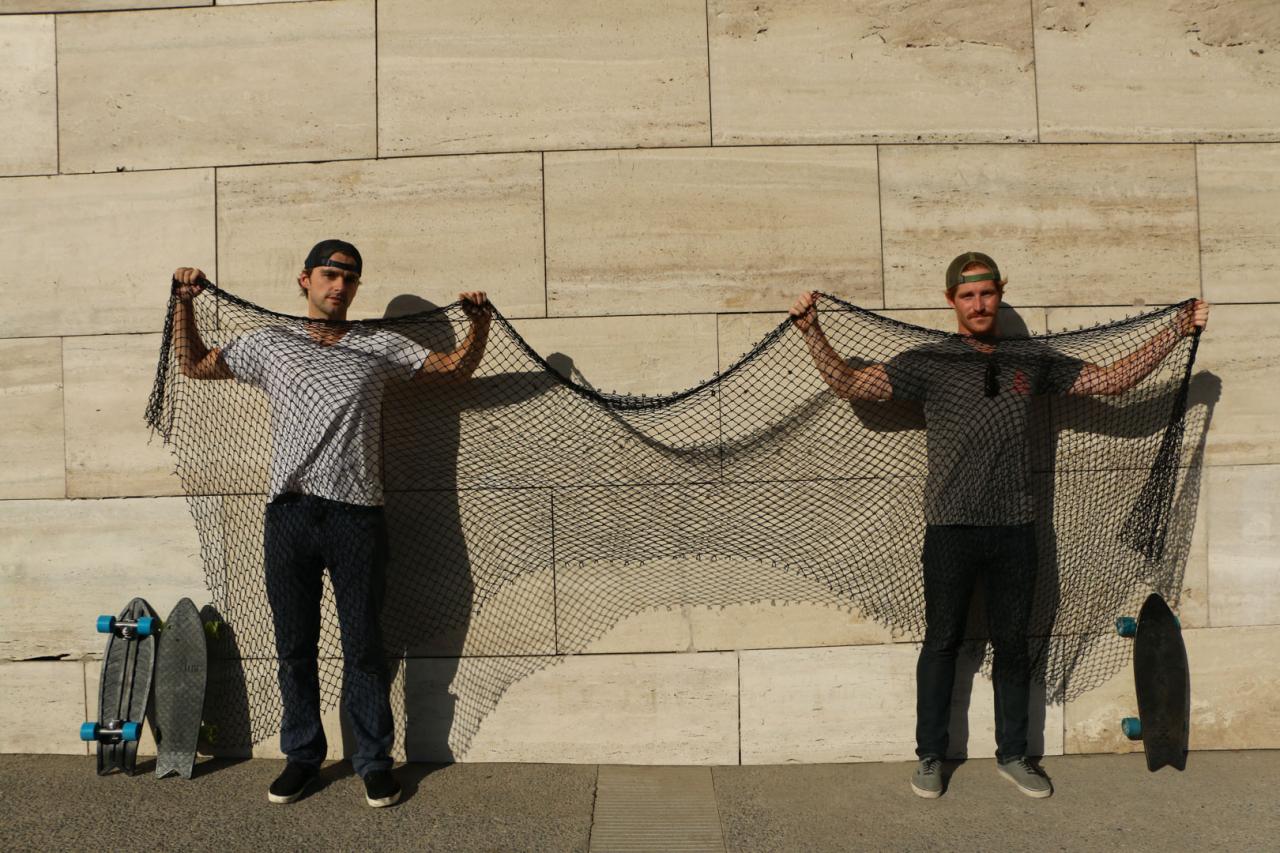

It’s April, the tail end of the harvest season. Each day, I accompany Arisa to the final stages of collection. Working as part of a larger team, our task is to collect and re-string the netting on which mozuku seedlings are grown.

Conversation with Arisa is sparse, as we share no common language, but it is undeniably warm. Relying on the metallic, monotone clang of the Google Translate app, we sit on the fiberglass floor of her skiff, passing my phone back and forth. Through this universal piece of technology, our separate worlds begin to make sense to one another. We exchange jokes, questions, and stories. Arisa is quick to laugh and eager to talk about her work. With the phone in hand, she instructs me on how to set nets underwater.

All of which boils down to: “Do what I do.”

With the boat anchored and wetsuits zipped up, we clench our scuba regulators tightly in our teeth and vault our bodies backward, tumbling into the saltwater below.

I note that industrial seaweed fields resemble traditional farmland.

Designed in rows, cross-stitch nets are seeded with mozuku spawn and “planted” into the barren sand flats near coral reefs. From the rippling water above, the fields of brown seaweed look similar to the sectioned-off structure of an unwrapped Hershey’s bar, with rectangular plots separated by thin strips of sand.

Beneath the surface, I swim behind Arisa, who, though twice my age, doubles my speed. Fast, elegant, and patient, she waits ahead of me. Through the mutated Morse code of underwater hand signals, she points to her eyes, then to herself, before taking off to unstring and gather seaweed nets.

“Watch me.”

A shared language hardly matters underwater, anyway.

Soon, I am beside her, gathering my own nets. Working hard not to tangle myself or my air tube, I kick forcefully to lose depth and keep the rapidly bundling latticework from snagging on the seafloor. Hours pass this way, zigzagging back and forth above the sand, untangling and organizing 50-foot webbing. As the season wanes, these nets will be hauled in and carefully inspected for the next harvest. Above us, the sunlight penetrates down. I turn and gaze at the gently lapping surface overhead, feeling the warmth of midday rays. In a moment of physical and spiritual suspension, I am held by the sea. I feel bliss.

Arisa taps my shoulder — it’s time to break for lunch. We swim upward. As our heads break through the tension of the waves, my ears fill with the sounds of hacking air compressors, clattering diesel engines, and fast-flowing water. We surface beside the main harvest vessel, where the rest of the crew is busy collecting seaweed. Thick black suction tubes snake from all sides of the boat, forming the stretched limbs of a bionic, octopus-like machine. This intricate apparatus powers the harvest. Beneath the surface, divers grip these winding hoses, guiding the open mouths of the pipes over the full-grown mozuku.

In an instant, the soft, string-like tendrils of the brown seaweed are ripped from their nets and whisked to the boat above. As with all perishable crops, seaweed especially, time is of the essence. These cuttings will be transferred into waiting plastic boxes and driven back to the island’s processing plant within the hour.

Though seldom seen on Western menus, mozuku seaweed thrives in the warm, nutrient-rich waters of Okinawa, where it has long been a staple at dinner tables. Celebrated as a superfood brimming with vitamins and minerals, its cultivation on an industrial scale is a relatively recent endeavor, spanning just 35 years. The boat I am on today will harvest several tons of mozuku, many times over. This seaweed will make its way back to the Okinawan mainland, where it will supply restaurants, bars, and supermarkets across the island.

Back in the water, Arisa and I pull ourselves into the harvest boat, muscles tired but steady. The captain, Isamu Nakayoshi—a kind, cheerful man bronzed from years on the sea—hands out bento boxes. Crouched in our open wetsuits, puddles pooling at our feet, we shake the water from our ears and lazily eat our lunches.

Isamu and Arisa’s paths crossed years ago, and their friendship was immediate, built on shared passions and mutual respect. Their connection to the island and its surrounding waters is unmistakable in the way their eyes linger on the horizon as we skim across the bay, and in the seamless rhythm they share beneath the surface, whether spearfishing or harvesting seaweed.

When Arisa first arrived on Kumejima, the seaweed and fisheries cooperative was an exclusively male domain. A diver and fisher herself, she was determined to join and harvest seaweed. However, her application was rejected several times, largely because of her outsider status as a woman. Isamu, already a respected captain and key member of the cooperative, eventually sponsored her application, making her the first woman to join — a milestone in the island’s history.

Since then, their collaboration has deepened. Together, they’ve worked on countless marine research projects, providing invaluable samples for visiting universities and researchers. They regularly venture offshore to hunt tuna, landing massive catches to sell in mainland markets.Their partnership reflects the profound ties between the people of Kumejima and the sea; a connection that transcends profession to define a way of life. This bond is embodied in the very dialect of the island prefecture.

The Okinawan word uminchu has no direct English equivalent. Most often, uminchu is poorly translated as “fisherman.” This interpretation paints with a broad brush, negating the deep cultural nuances of the term and its indistinguishable ties to Okinawan identity. A more accurate interpretation of the word is something akin to “born of the sea” or “person of the sea.” In a pinch, the multi-hyphenate “fisher-sailor-diver-swimmer-spear fisher-shell harvester-seafood lover-ocean lover-seaweed harvester-and more” might also suffice. For Okinawans, and particularly for the people of Kumejima, an island formed from ancient coral reefs, the sea is a fundamental part of their cultural identity and self-understanding.

The Ryukyu Island chain in the Okinawan Prefecture, where Kumejima resides, is dotted with coral-based isles and atolls. Over the course of millennia, these islands have uplifted and taken shape, softening the once rigid boundaries between land and sea. This unique geography is a hallmark of the Okinawan region, marking it as distinct in both environmental and cultural heritage. These islands rose from the labor of living marine organisms, their foundations carefully crafted by coral.

Quite literally, sea life begot terrestrial life — uminchu exemplified in geology.

The word “fisherman” can never fully capture the nuance and intensity of these islanders’ reliance on and connection to the ocean. Arisa and Isamu stand as shining examples of uminchu. They don’t just harvest seaweed. They hunt tuna, spear fish, scuba dive, conduct ocean-based research, and handle boats with the ease of those born to the water.

Unlike the English translation “fisherman,” the Okinawan word uminchu does not denote gender. Anyone can “be of the sea.” As a “birthplace,” the ocean makes no distinction between those who engage with it or belong to it. Even in the literal structure of the word, no value is placed on sex, only on the connection forged with the water. Despite this, during my time on Kumejima, Arisa was the only woman I saw in the seaweed harvesting grounds.

Yet I’m told that Arisa’s integration into the cooperative has sparked something of a quiet revolution, inspiring several other women to join. Though their numbers remain few, their presence is undeniable. They are uminchu.

After lunch, we plunge headlong back into the sea to continue our work. As the hours pass, the sun begins to dip, signaling our eventual rise to the surface and the end of the workday. We clamber back into the skiffs, the mozuku now harvested, the nets set and hauled in. Wet, tired, and content, we haul anchor and turn the boats toward shore, watching the shimmer of the submerged coral reefs drift away.

The rhythm of the harvest will unfold like this for days and weeks — a steady, unbroken cycle.

Through my time spent with Arisa, I have come to see how fully she represents the spirit of uminchu — a deep bond with the sea that transcends societal boundaries. Her integration into the male-dominated seaweed cooperative reflects a broader shift in Kumejima, where the ocean’s pull is proving stronger than traditional gender norms.

At the dock, we unload our salt-stained buckets and strip off our wetsuits. As she makes her way to her car, her shoulders tired but held high, Arisa stands as a beacon of inspiration in a once-closed industry. In a place where the tempo of life is determined by the tides and the harvest, Arisa, like her male counterparts, proves that the sea’s call is for all who choose to answer.