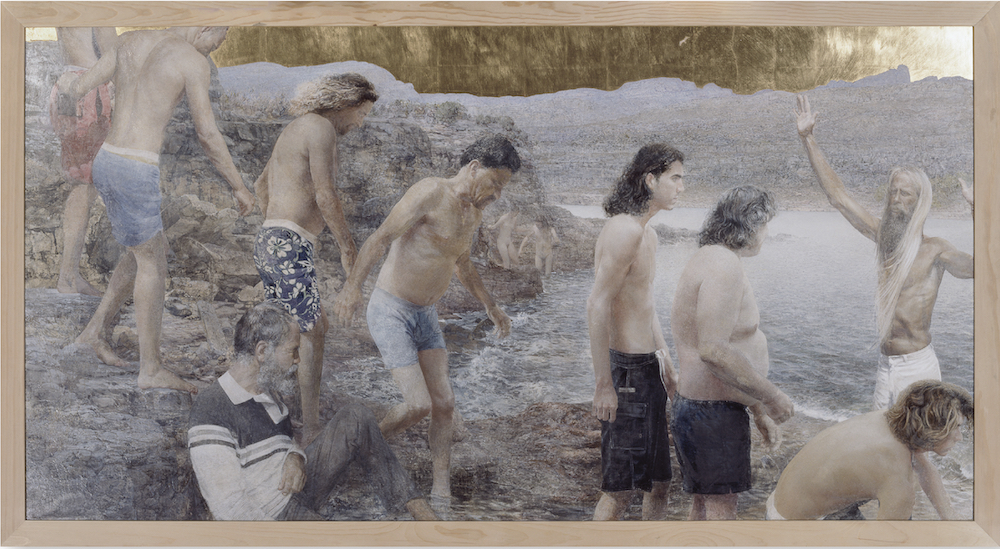

“Baptism by Water” is a 20th Century painting by artist John Patrick Cobb, an artist who is very much alive. He is also a surfer.

The story you’re about to read follows the history of water from its biblical origins to our everyday sessions. Through a contemporary lens, the central figures in this painting (Christ, John the Baptist and Jonah) are wearing ordinary swim trunks. Adam and Eve can be seen in the background. None of them are in Jerusalem, but at a popular swimming hole called Hippie Hollow in Austin, Texas.

I have heard it countless times: “Surfing is religion” or “My religion is surfing”. Only this time, paired with this painting, it hit differently.

This story does not unfold on a Sunday morning in the water, nor before or after a clean swell. In fact, it began one hundred and fifty miles from the nearest ocean in a small museum in Austin, Texas.

The artist, John Patrick Cobb, an aging surfer, was explaining the ideas behind a dedicated series of paintings. Work that has taken him four decades to complete is now displayed in a wooden chapel he constructed himself by hand. At each end of the chapel stand the two largest paintings. On one end, “Baptism by Fire”. On the other, “Baptism by Water”. Each painting is thoughtfully displayed alongside the scriptures. Each artwork was crafted using one of the oldest painting methods, known as egg tempera, or the mixing of powdered pigments with the yolk of eggs.

How does it correlate? The way we feel as surfers after being in the ocean must resonate with a traditional baptism after a “salt water rinse”. It represents a renewal of our spirit. It offers us new lenses to go out into the world acting and seeing perhaps better than before. That must be one of many reasons seven of the eight people in the painting “Baptism by Water” are surfers.

The leading figure portrayed as John the Baptist is, in reality, a surfer. His real name is Wes Beck, a rather obnoxious surfer the artist recalls. “He was the loudest surfer in the lineup” says Cobb. When surfers pack together on a peak, each vying for position on the next wave, a loudmouth is almost guaranteed to be something we have all experienced at one time or another. The artist chose this individual for his loud voice. I frequently think about something Cobb told me about this particular surfer. It went something like this: “If he would only use that voice for good, think about what he could do?”

This is a recurring theme in “Baptism”. At the bottom edge of the painting Cobb depicts an actual homeless man who lived under the seawall in Galveston, Texas. During the day, this fellow would drink heartily and yell at the cars. Cobb, at the time, lived across the street and would bring him coffee on blustery winter days. A year or so passed before Cobb asked the fellow to pose for the painting.

“Somebody like that is so desirous of the spirit that they deserve to be in there, even if they acted in a way that’s contrary to it. What a man like him really wants all along is to be a part of something, and instead - due to their lifestyle - they are in eternal frustration,” says Cobb. “It’s a choice that everybody makes, to participate or not, but imagine if you could make that choice for somebody else? His representation in my painting would be the choice I would have for him”.

Jonah the Prophet in “Baptism” is portrayed as crouching down. Like the homeless man, he appears disobedient to the calling from John the Baptist. The man depicted as Jonah (who, in reality, happens to be named Jonah as well) is also an excellent surfer. His demeanor is quiet and focused. Some may think he is arrogant, but that is not the case. This demeanor you might find in elite members of the military who have paid their dues, any former prowess is now hidden behind kind eyes and a charismatic smile. A man like Jonah rarely mentions his achievements or his suffering.

Artist John Patrick Cobb and surfer Jonah’s father (Glenn Francis) are close friends. Glenn is also an artist and surfer of high caliber. The first time I met Glenn Francis he tried to explain transcendental thinking to me. His leading concept was that everything we think and do is not free from influence. Wanting control and making sense of random acts in our lives is a natural human reaction. In similar surfer thinking, the unruly ocean is never there to conquer, but rather for us to find peace in its chaos.

The biblical Jonah found peace amid chaos. He insisted on being thrown overboard during a horrendous storm at sea only to be swallowed by a whale. He spent three days inside the belly of that whale protected from the chaos of the storm.

On one day in the water a surfer may feel blessed, calm and strong. On another day he or she might be frightened to the core, appearing weak and small. Many surfers resort to ‘foxhole prayers’ in those moments, perhaps promising that if allowed to return to shore safely, life will start anew. At that moment, whether you are ready to admit or not, you were begging for forgiveness.

The history of salvation in water works for both its cleansing and treacherous qualities. The biblical Jonah's act of courage amidst the chaotic tempest by sacrificing himself to water saved him in the end. That, in turn, saved others.

Suffering is something we all have in common, whether surfers or not. Perhaps that’s why at the end of every session surfers discuss the hold downs, and share stories about overcoming fear. We might talk about painful training days finally paying off. I once heard an athlete refer to his scars as “life tattoos”. Each scar comes with a story. We all come with a story. Searching for the perfect wave is an endless quest. In reality, there is no endless summer, no perfect wave. There is a lot of driving around, flat tires, broken leashes, dinged up boards, harsh cross currents, strong winds, and maddening crowds. We spend countless hours researching storms, experiencing brutal travel, spending our time away from family. There is money (so much money) spent on boards, travel, food and drinks. We have little to show for it. But as we grow older, our wrinkles represent a roadmap of a life well-lived.

One of the very real powers of a painting like Cobb’s being published in a watersports magazine read by surfers is to remind us that we are all connected. As surfers we travel, we get to know the beaches, waves, and people from foreign lands. We get to know their histories. We share a fascination with fellow seafarers and how they live and who they are. We learn about one another.

How do a bunch of surfers and a plumber become immortalized in a religious surf painting like “Baptism by Water” by John Cobb? Together, we look for the light. We are able to treasure moments. We believe in things that are hard to describe, and most important, we suffer well together.