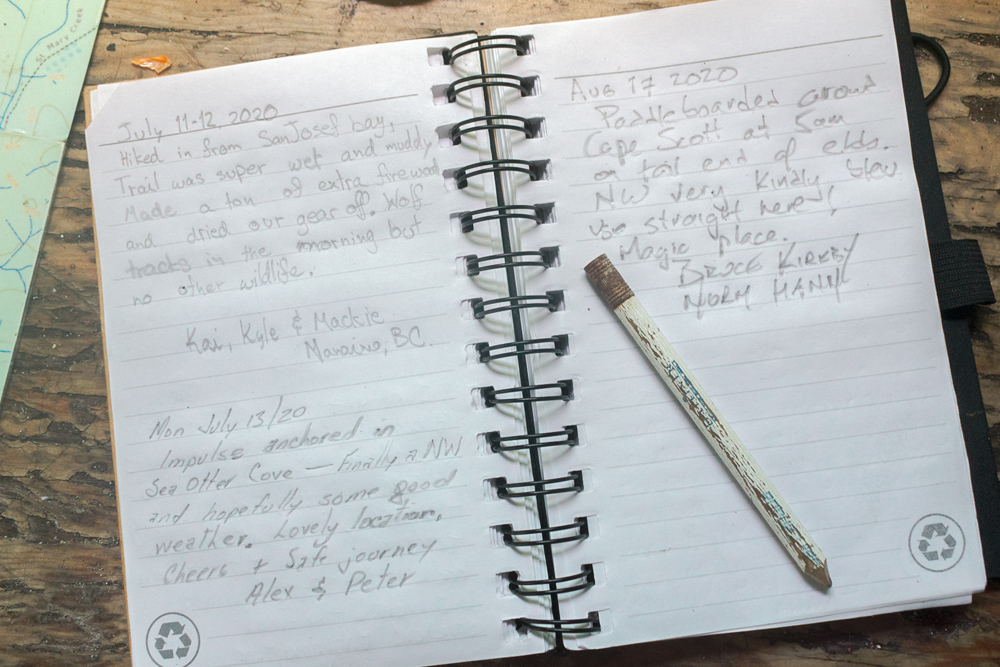

Northern SUP expedition traveling partners Norm Hann & Bruce Kirby follow the water trail of BC’s First Nations people around the horn of Vancouver Island.

Unbeknownst to us, a southwest gale had been blowing for days. A dark, muddy rainforest trail led my partner Bruce and I out to the Cape’s rocky headlands and to a sight neither of us had seen before. The ocean was heaving as dark, green mountains marched toward us, rearing up as they hit shallower water, some breaking far offshore, others exploding skywards. For a long while we sat transfixed, humbled and intimidated. Clearly we were not paddling around the cape anytime soon, if at all.

Hazard to Mariners: Treacherous Waters of the Cape

Ever since I moved to British Columbia from my home in Northern Ontario and first laid eyes on a nautical chart of the west coast of Vancouver Island, I have looked at the headland and the fabled, treacherous waters of Cape Scott, and wondered what it would be like to paddle around this land mass. The Cape, on the Northwest tip of Vancouver Island, is a wild and raw landscape that showcases the immense power of the Canadian coastline. It is rich in legends and stories of the Kwakwaka'wakw First Nations people. The Cape Scott lighthouse here has recorded wind speeds well over 160km/hr and seas greater than 30 meters. The dynamic and potentially terrifying conditions on this peninsula have made ‘rounding the cape’ a major paddling accomplishment.

Bruce Kirkby, my trusted expedition partner for the trip, is an accomplished adventurer. He is widely recognized for extended expeditions to remote wilderness areas, usually with family in tow, as documented by his most recent book, Blue Sky Kingdom: An Epic Family Journey to the Heart of the Himalaya. A few years back, Bruce paddled this section of coastline solo but a heavy fog shut down his attempts for a safe rounding of the cape. He was motivated to have another go. I was fortunate to have his experience, decision making prowess and friendship for the journey.

Getting Into Position

Under sunny skies and building winds, we launched our fully loaded touring paddle boards from the coastal logging and fishing town of Port Hardy on the northeastern shores of the island. We spent the next day and a half paddling north through the wind-generating tunnel of the Goletas Channel. We passed killer whale rubbing beaches and navigated around Tatnall Reefs and the treacherous Nawhitti Bar. The farther north we paddled the more exposed we were to the vast waters of Queen Charlotte Sound, but it felt great to be on the water and immersed in the rugged coastal wilderness.

We used tides, currents and low winds to make our way around Cape Sutil, the northern tip of Vancouver Island and one of the most scenic beaches on the coast. Cape Sutil was once a fortified village, named Nahwitti for its chief. Eventually, that name was also bestowed on its people. As much as we wanted to stop to explore and search for petroglyphs, the ancient rock carvings made by the Nahwitti, we carried on knowing from experience on the coast that when conditions are good, miles need to be made. From Cape Sutil we could now look west and it was the first time we could see our objective, Cape Scott, with clear views beyond to the ominous and remote Scott Islands. With a low swell, clear waters and flat conditions we moved west and made our way past a pair of feeding humpback whales to land at our second campsite at Shuttleworth Bight.

“On the water early, off the water early” is a common saying for west coast paddlers which helps to avoid the daytime winds that can quickly build the sea state and generate challenging conditions. Adhering to this rule we made our way past hikers slogging along the popular North Coast trail as we travelled offshore, sharing the water with rafts of sea otters that watched us from their backs with curiosity. But as we got closer to our last point of shelter before committing to rounding the Cape, strong winds buffeted us from the south indicating unforeseen challenges ahead. We landed on Experiment Bight, a place referred to by the Nahwitti people as “Whale Between on Beach,” most likely in reference to an ancient traditional whaling location. In less than 48 hours and 80 kilometers after starting, we were now in position. Cape Scott was close enough to touch.

Reflecting and Connecting: Nahwitti Lands & Lifestyle

Shortly after our hike out to the cape which revealed intimidating conditions and treacherous waters, we headed back to our campsite to wait out the storm. Bruce and I spent the day searching for sea glass and exploring the incredibly unique ecosystem of the Cape.

The more time I spent on the land and reading the history of the place, the more connected I felt. According to the Nahwitti People who inhabited this area, the unique sand neck or isthmus, connecting the northern waters of Queen Charlotte Sound with the west coast waters of Vancouver Island, was referred to as “against each other.” This was also the natural overland route for the Nahwitti who carried their canoes across the short portage from Experiment Bight to Guise Bay, to avoid rounding the treacherous headlands. The cape had names like “foam place,” “sea monster,” and “swell on beach,” referring to the heavy sea states found here.

Most fascinating is a place called Ouchton, an ancient village site referred to as “those of the unprotected bay.” Ouchton was fortified and tucked away in jagged sea cliffs from the heavy swells. I wondered how anyone could survive out here. This place had already laid waste to Danish pioneers who regretfully tried to settle a community at Ouchton in the early 1900’s. For us, the cape was “remote” yet this was “home” for the Nakumgilisala People who spent their summers harvesting and gathering food in this challenging environment. An area of immense power, it was clear that the spirits were present and the ancestors were watching. Later that evening after listening to the weather radio, watching the natural cues and processing our thoughts and emotions, we made the decision to paddle around the cape the following morning.

Rounding the Cape

Bruce and I, too energized to sleep, were moving well before our alarms went off at 4 am. Darkness greeted us. Winds had favourably shifted to the northwest as we quietly loaded up our boards, deep in thought and anxious about the next hour. At the break of dawn and just before 5 am we pushed out through knee high surf. We were headed around the cape and within minutes we’d reached the point of no return. We were committed. The stiff northwest wind was generating a chaotic three foot chop and, even more unsettling, the southwest swell had not eased overnight. Large sets rose from the ocean at three meters high and built to bigger waves in the shallows.

“There was no discussion. The situation wasn’t ideal but it was within our abilities. Without a word, we kept paddling, entering a world of black, grey and white. Ghostly waves exploded upwards around us. The tide turned, slowing progress. Shouting, we discussed angling inside a scattering of offshore rocks. Then a monster swell reared up and broke, exactly where we were headed. We pointed our bows out to sea to escape the tempest. We decided to go outside of the breaking swell and currents. Surf scoters streamed past us at waist height, in long lines reminiscent of smoke. A wave caught the tail of my board, sending me tumbling forwards. Then I was underwater. Silence, and up again.

“You OK?!’ Norm yelled, but I was already paddling, proving a long held theory that paddleboards and the ability to leap back on have great advantages in serious situations. The wind kept blowing us south. Brace, paddle, brace. At some point we realized we were beyond the danger and we rafted up, tiny corks tossed on a massive ocean. Norm’s eyes told the story. We’d experienced something quasi spiritual in those few kilometres.” - Bruce Kirkby.

Two hours later we attempted a bonafide surf landing with loaded expedition boards at Lowrie Bay. We set up our beach camp under the warmth of a midday sun.

In times of intense focus and being in the zone, memories and feelings are etched in your psyche. In the midst of the chaos at the cape, what I remember most were the commitment of those first few paddle strokes leaving the beach, the surf scoters flying close by as they made their way out to offshore feeding grounds and the waves rising up and crashing against the rocks. But the one moment in time that made me smile the most was looking back at Bruce, who - focused and committed - was making his way slowly past the Cape as the blood red light of a coast mountain sunrise lit up the world behind him.

A Beautiful Finish and an Invitation to Keep Paddling

On the beach at Lowrie we rested, knowing that we had successfully rounded Cape Scott. We both felt fortunate and expressed gratitude with a nip of scotch as the sun dipped below the horizon. We slept well that night.

A short paddle from Lowrie Bay in calm winds and low southwest swell the next morning put us around the challenge of Cape Russell as we made our way to the Helen Islands at the mouth of Sea Otter Cove. Fog arrived after setting up camp and we spent the rest of the day beach combing, drinking coffee and sharing stories.

On our final morning, we approached the calmer waters of San Josef Bay and surfed knee high waves into the clear and tranquil waters of the river. It was calm and quiet. Only the sounds of birds and our paddle strokes highlighted the stark contrast to the last few days of exposed, wild water paddling. Like most great adventures we did not want the trip to end as the coast has a way of inspiring you to keep going.

We made our way upriver, past towering sitka spruce and lush temperate rainforest. It was the perfect ending as our north coast journey released us.