In the days before power boats, ferries and bridges, transport between islands of any archipelago relied on paddle crafts including hand dug canoes, kayaks and rowing boats. Later on, the pull to explore one’s homeland by sea became a mythic adventure where men and women would take to the water to gain a broader perspective and understanding of the lands in which they lived. Island chain crossings have remained a popular means of transport for many centuries among water people around the globe. In our recent culture, the renowned Molokai 2 Oahu crossing of the Ka’iwi channel or “Channel of Bones” has become an annual rite of passage for the water tribe, representing a certain level of aptitude for open water crossings by prone paddlers, stand up paddlers, outrigger canoe paddlers, foilers and, more recently, wing foilers. As any true waterman or waterwoman will tell you, the accomplishment is in the path itself. The reward is in the journey. We struggle to earn the skills and training to become proficient enough to try an open water passage. That is the mark of a true water lover.

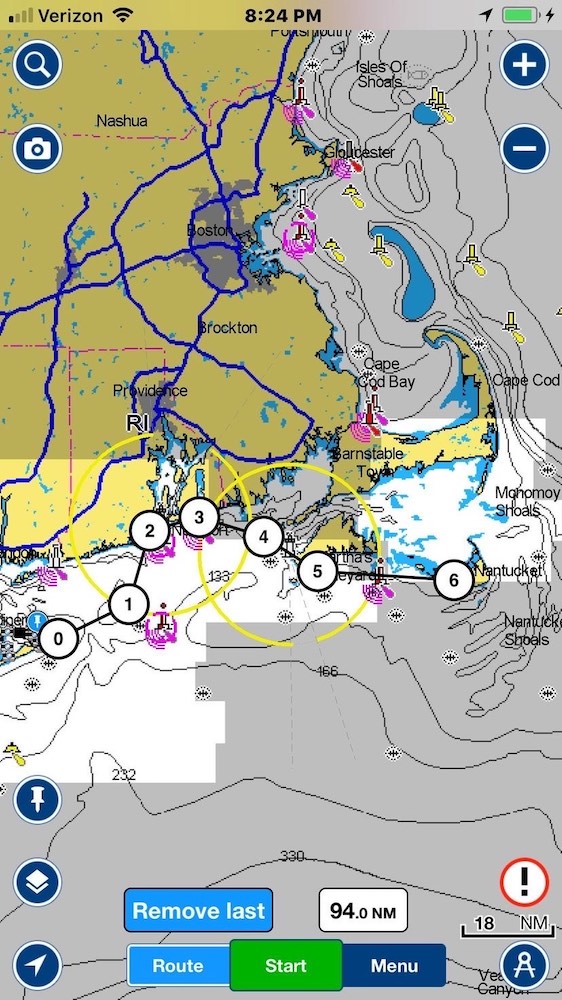

So here we are, three friends, three men, including myself (Patrick Broemmel of Massachusetts), Will Rich of Hawaii and Jeremy Grosvenor of New York. We decided to take on a northeast island chain crossing in a three-man outrigger or “sailing canoe”. Launching from Montauk Point, NY, the destinations on our journey included Block Island RI, Newport RI, Cuttyhunk MA, Martha’s Vineyard, MA, and finally Nantucket, MA, after a four-day open water crossing that brought the three of us on an adventure we won’t soon forget.

- Intro by Evelyn O'Doherty

Holopuni - which in Hawaiian means "to sail everywhere" - is the original name given to the 3-man outrigger canoe used to explore the coastal areas of the Hawaiian Islands. The Holopuni OC3 Paddle and the OC3 Sail are the three-person, 30' Hawaiian outrigger canoes that have evolved since 1981 to meet the many challenging needs for paddling, sailing and camping in the wide variety of conditions found in waters worldwide.

The idea for a northeast island crossing trip started with a text conversation between Jeremy Grosvenor and myself back in February 2021. Still in the throes of the COVID shutdown, we were talking about trips and he sent me a picture of a proposed water route he had attempted in the northeast back in 2013 but was unable to finish when his crew had to return home mid-voyage. The wheels began turning. We agreed that it was a great plan and that we would attempt the passage in the coming summer. We needed a third person, so I sent my good friend Will Rich a text with the details. In true Will fashion the only thing he asked was, “When are we leaving?”

Later on, I would realize how important it was to select the right people for a journey like this. A holopuni voyage, especially one with open water crossings, is not a trip you take just anyone on. It requires very specific skill sets and attitudes for when things get interesting.

I knew Will was a good choice. In 2011 he and Mike Simpson paddled stand up paddle boards and camped from Key West, Florida to Portland, Maine, the first journey of its kind on SUPs. He mentioned in our initial talk that on their trip they had taken the coastal route around the islands we were planning to visit and he’d always wanted to go back and see them. I knew from previous experience that even under the most adverse conditions, Will’s approach is to simply put his head down and go to work until the task is complete. No quitting, no complaining.

Neither Will nor I had ever been on a trip with Jeremy, but we knew of his reputation and that was enough. He would never admit it but he's a bit of a mythical figure around the northeast ocean sports community. A dozen Kaiwi channel crossings on prone paddleboard, OC1 and OC6, half a dozen Catalina crossings, outrigger, 4 man surf canoe sessions, solo in maxing winter surf, prone surfing, SUP surfing, body surfing, mat surfing, foil surfing, wing foiling, windsurfing, sailing, downwind foiling, diving, winter swimming off Long Island, NY (in water of 0 deg C wearing only speedos and a swim cap), swim camping...the list goes on. He's like an ocean sports version of Yoda, living in relative obscurity, surfing and paddling far from the crowds at out of the way places on the tip of Long Island, a place no one would expect to find someone with such a skill set.

The next few months were filled with group texts and emails going over gear lists, logistics and locking down the dates until finally the day came and it was go time. Will flew into Boston the afternoon of July 22, 2021 where I picked him up in the U Haul van I rented after my own truck started to act suspicious just days before I was scheduled to leave. Numerous calls confirmed that there were no rental cars available on all of Cape Cod since it was the middle of July and peak summer season. so a box truck would have to do. Driving into a major airport and doing

laps around the terminals in a UHaul while your friend waits for his bags is quite an experience.

Finally Will informed me that his bags had appeared and after a stop for food we headed south towards our departure point of Montauk, New York. We would stay at Jeremy’s en route and leave the following afternoon, hoping to ride the outgoing tide east towards our first stop of Block Island, RI.

DAY 1: Montauk, NY to Block Island, RI - 18 nautical miles

The next morning we were up at 5AM and on the road early, headed for the boat ramp in Lake Montauk where we would set up for launch. The traffic was already starting to build as we pulled over to get coffee and stock up on beans for the trip. A crew of cyclists in their spandex outfits had assembled in front of the coffee shop and shot us suspicious glances as we moved the traffic cones out of the way to park our 50 foot rig in the no parking zone out front.

We arrived at the town ramp in Montauk just after 8AM and ended up assembling the majority of the boat on the trailer because there was no beach to set up, and the water off the end of the ramp was too deep to stand in. It worked out in our favor, though, as we adjusted the lashing points to ideal working height by tilting the boat within the cradle on the trailer, thus eliminating the need to work off the ground.

Then Jeremy left to head home to park the truck and hitch a ride back with his wife, promising pizzas when he returned.

We were looking at a 20-mile crossing in a boat none of us had really paddled before, but we were excited to go and Jeremy made good on his promise of pizza when he returned. We pushed away from the beach, waving to Jeremy's wife Saskia and a few other friends who had gathered to see us off.

I was given the first shift at the helm. Paddling out of Montauk harbor, we probably looked like a drunken snake weaving our way between large power boats and a few commercial fishermen who gave us the look as if to say, “Here we go again. Summer dinks. Might as well call the Coast Guard now.” We managed to make it out to open water and were finally on our way.

The first hour was spent figuring out how the boat handled. We had almost no wind, so Will and Jeremy paddled while I attempted to keep us on a straight line. As we neared the eastern end of the peninsula, Block Island came into view on the horizon and the southwest sea breeze we had hoped for began to fill in.

The boat suddenly came to life. As the sail filled we dropped the centerboard and the boat that just a few minutes ago was zig zagging across the water locked in and was sailing a straight line at 7-10 knots under a light breeze. Will jumped out on the tramp and Jeremy produced a cheese pizza from somewhere and we passed it around, celebrating our good fortune.

We made camp for the night on an isolated beach on the west side of the harbor entrance where we ate freeze dried chili and smoked mackerel before setting up camp and going to bed.

DAY 2: Block Island, RI to South Beach, RI - 15 nautical miles

We left Block early with a group of sailboats doing our best to make way towards Point Judith on Rhode Island’s mainland, but the wind had shifted to a more northerly direction making our path almost directly into the wind. Will did a great job tacking back and forth as we made our way up Long Island Sound, attempting to pass the northern corner of Block where we would take a slight right and head towards the mainland.

About an hour in, we rounded the corner and paddled into the famous (but unbeknownst to us) North Rip and a rising tide, which made it seem as if the entire ocean was desperately trying to return to Long Island Sound but in the opposite direction that we were going. With little to no wind the only way through was to paddle...hard.

To the East, across the rip, we could see clean water and thought if we could reach there we'd have a much easier time paddling, so we really started to put power to the paddles. We began punching through chop and dropping into troughs that were getting more and more precarious the closer we got to the edge of the shoal. We were maybe doing half a knot at full power against the current, slowly creeping towards the calm side of the rip.

Within a few meters of reaching the other side of it, the standing waves went to the next level. The boat would teeter between peaks of the standing waves, then drop into a trough where the water began to come completely over the gunwales flooding the entire deck. Without sprayskirts on we would have been in a bad spot. Even with them in place we took a substantial amount of water in the boat so I stopped paddling and grabbed the pump to try and stay ahead of the situation. We agreed that we needed to get the hell out of there fast, so Will got us turned around and we paddled with the current until we were clear of the rip. We moved on against the tide, slowly making our way east for about two hours when we decided to stop and let Jeremy take the helm.

Just off Narragansett, RI we heard thunder and noticed a big, dark patch of clouds with rain visible to the ground coming from the west beyond Newport. It was heading our way and with it came the wind. The sail was trimmed and we began to make progress when we noticed a sailboat that seemed to be following us. It was under engine power and came up on us quickly.

A man stood on the rail and shouted over “Are you OK? We saw the...” he made paddling motions with his hands. We looked over, a bit confused, “Yeah! We're fine! Thanks for checking!” There aren't any sailing canoes in these waters, so I guess he did the right thing by wondering about us.

We began a more easterly direction to pass south of Aquidneck Island in hopes of reaching Newport’s Third Beach before the storm caught us. As the storm neared, the wind became stronger until we had a solid 15 knots blowing from almost directly astern. The boat again came to life.

As the swell built, Will led the charge from seat one where he masterfully synced our strokes with the running bumps and Jeremy steered us with the precision of a surgeon. We were surfing. Like real honest to God, they put the 30 foot boat on the face of the waves surfing. It was incredible to experience. Three guys, the boat, the sail, the wind and the swell were entirely in sync.

We covered about 4 miles in 30 minutes and before we knew it, we were closer to Little Compton than Newport. Flying past Sakonnet Point, the first point of the mainland east of Aquidneck Island, we could see our destination a few miles ahead. Sailing through huge balls of menhaden with birds dive bombing them, we reached Chase point and turned left up into the cove where we ran right up on the beach at South Shore Beach Park. Here we feasted on chili and mackerel, just as a double rainbow appeared right over the mast of the boat and the sun began to set behind the fading storm clouds.

Once the boat was secured, Jeremy pulled a surf mat and a pair of fins out of his bag and within minutes had the mat inflated and was heading out for a surf in the nicely shaped waves. We watched him get covered up a few times before heading to the parking lot about a quarter mile away.

Will had called ahead to our friend Mimi Whitmarsh and she met us an hour later bringing food and water plus a vehicle which we used to drive to the local market to fill our bags with additional food for the rest of the journey. The day ended with chili and Mackerel - which we ate like starving dogs. A double rainbow appeared right over the mast of the boat as the sun began to set behind the fading storm clouds.

DAY 3, Route I: South Beach, RI to Cuttyhunk, MA - 12 nautical miles

Reflecting on our previous experience with the shoals, we determined we should probably pay a bit more attention to the tides, so the next day we were up at 4AM making coffee and breaking down camp for a 5AM departure. Our path would take us east about four miles, skirting south of Gooseberry Island, crossing into Massachusetts, then on a more southerly track across the mouth of Buzzards Bay to the Island of Cuttyhunk. We timed our traverse of Buzzards Bay so that we would be crossing just as the tide had ebbed completely and began to flood east back into the bay. We were learning.

As soon as we passed Gooseberry, MA an unexpected east wind came over our port ama and the sail filled, once again allowing us to relax and enjoy the sunrise as the miles flew by. We made the entrance to Cuttyhunk harbor in under two hours, from stepping off the sand in Rhode Island, a distance of just over 12 nautical miles. As we sailed into the harbor every head turned and stared. This continued until we reached a small backwater within the harbor where we tied up and came ashore.

Cuttyhunk is a place out of a movie. There are only twelve (yes,12!) year-round residents, about 100 homes and a total land mass of about 580 acres. The island population swells to a few hundred in the summer months, most - if not all - coming by boat. On the dock was an ice vendor, a small take out cafe and a tackle shop which was closed. Up the street we were told there was a small store and a t-shirt shop. That was it as far as businesses went. Exploring Cuttyhunk took 2 minutes.

Small groups were gathered around a few tables for coffee and conversation at the town’s one coffee shop. Everyone seemed to be as happy as we were to be there. We sat on the dock eating warm egg sandwiches and, when finished, went back for seconds. Someone pointed out a salty old fisherman and told us that the previous winter he had frozen his beard to a winch on the deck of his boat and simply pulled out a knife and sawed through it to free himself.

Back at the canoe we hung our wet clothes across every available surface and toyed with the idea of renaming the boat “Yard Sale”. We even typed the words into Google translator to see what “Yard Sale” would be in the Hawaiian language. “Type in ,To display one's possessions for the purpose of selling them.” I yelled to Will laughing and assuming there was no such thing as a yard sale in ancient Hawaii.

Once back at the canoe, it wasn't long before people began to stop by and ask questions.

“We saw you come in this morning! What is that thing?” seemed to be the same words out of every person's mouth, wondering what exactly we had sailed in on. An hour or so passed as we answered questions about our journey and sought information about the tides, trying to plan the rest of our day and the crossing of Vineyard Sound where we would reach the island of Martha’s Vineyard and our next stop for the night.

Everyone seemed to have a different opinion regarding the tide. Apps were referenced, the Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book - which Jeremy had brought- was sighted many times, but with no consistent answer. Eventually, the decision was made that we were better off heading into the unknown than spending the day answering the same questions over and over again, so we packed up and paddled our way out of the harbor and into Buzzards Bay.

Day 3, Route II: Cuttyhunk, MA to Martha’s Vineyard, MA

We took an easterly route along the northern side of the Elizabeth Islands, staying out of Vineyard Sound and the exposure it would subject us to had we misread the tides. Which, by the way, we did.

The Harbormaster on Cuttyhunk had been correct in his reference to the tides running West and again in the opposite direction of our travel. Thankfully, this time the current was light enough so that we could still make good progress to the east, but boat traffic increased as we got closer to Cape Cod. Large boats began to buzz by us at what seemed like sixty second intervals.

The trip along Nashawena island and across the channel of Quicks Hole took about an hour and, while crossing the channel, the already complex tidal flows of this area confirmed their reputation when we discovered a northerly flow running between the islands.

Pasque Island went by quickly. As we approached Robinsons Hole, the channel between Pasque and the larger island of Naushon to the east, we could see that the current here was substantially stronger than the previous channel. This was due to a narrower opening and a pinch where the land on both islands seemed to reach out like fingers pointing towards one another. Under full power we were barely making headway trying to overcome the rip that separated the waters of Vineyard Sound from Buzzards Bay.

Will steered us into an eddy on the west side of the Sound where we made our way through a shallow patch of water and could chart our progress along the sandy bottom as stones passed beneath us and the sea grass flowed in the opposite direction with the tide. We finally punched through the last bit of rip and within minutes we were free and into the waters of Vineyard Sound.

Once again, the southwest sea breeze began to fill in so I jumped out on the tramp to relax and enjoy the crossing as we headed due east towards the northern shore of Martha’s Vineyard.

Progress was slower than expected as the wind came and went and we traveled against the current. Eventually, we approached the northwest corner of the island known as West Chop. To our left, we could see the infamous Middle Ground shoal and rip. We stayed close to shore, maybe 100 yards off the beach, in an effort to navigate the rocks and currents that were flowing briskly around the point. We watched dozens of sailboats with spinnakers unfurled make their way out and around the shoals. It turned out we were watching the annual “Around the Island” race! We also watched in amazement as large power boats filled with intoxicated summer folk flew past us at full throttle, some coming within a dozen yards of us.

Making it around the corner and into the channel between West and East Chops, it seemed as if we had entered a major US interstate highway. Only instead of cars, we were surrounded by amateur boaters with no sense of courtesy, or common sense, or sea conditions. This was unlike anything we had seen in the days prior. It was pure chaos and the most unpleasant time of the whole trip.

At this point we had been on the water for close to ten hours and we began discussing where we should come ashore for the evening. The original idea was to drop south and stop at the far eastern corner of State Beach to camp; however, that course would take us straight into the wind and would require another two to three hours of beating our way upwind. Our current line had us directly on course for Cape Pogue, the northern corner of Chappaquiddick Island, which was our jump off spot for our final passage to the Island of Nantucket the next morning, so we decided to stay on course and make that our home for the night.

With the end of a long day within reach, Will and Jeremy leaned into the paddles as I steered and we made short work of the 4 mile crossing, hitting the sand forty minutes after making the decision to go there. We rolled the boat up the beach. “We made it!” texts were sent. Again, under the setting sun, it was good conversation and freeze dried chili with smoked mackerel for dinner.

DAY 4: Martha’s Vineyard to Nantucket, MA

Up early the next day, we had coffee and breakfast before going over the boat one final time. On water crossings of this nature it is critical to make sure everything is tight and lashed down properly. Our trajectory that day would be the most technical crossing of the trip.

The waters between Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket - and this channel in particular - are littered with transient shoals, shallow sand bars that move and change depth with each passing season. There are also wicked currents. Many unsuspecting and inexperienced boaters have lost their boats and lives around these treacherous waters.

Rumor has it that a person could be sitting in calm seas, happily fishing away, when the tide turns or they drift a bit without realizing it and then, the next thing they know, there are standing waves coming over the side, rolling the boat.

We consulted the chart, determined our line - there was no land visible from where we stood, just empty horizon - and pushed off the beach heading at about 100 degrees towards Nantucket harbor.

It wasn't long before we found ourselves navigating the shoals. At times the water was so shallow we could clearly see the sand bottom, crossing from smooth flowing patches of water over the bars, back into steep chop along the edges.

After about an hour, we saw our first sign of land. It appeared to be the lone building on the tiny Island of Mukeget which lies about 8 miles southeast of Cape Pogue and 9-10 miles west of Nantucket harbor. We were farther north than we had hoped, but still on what appeared to be a good course. Not long after spotting Muskeget, the island of Tuckernuck came into view which is at the west corner of the main island of Nantucket. Then we spotted the big water towers on Nantucket itself.

The wind was really picking up. At this point we were about 8 miles northwest of Nantucket proper and directly over the Tuckernuck shoal which, in combination with the strengthening breeze and ebbing tide, was creating some technical sailing conditions.

Will spotted the Great Point lighthouse sitting at the northern tip of the island and marking a kind of do-or-die heading for us. We needed to stay south of that point in order to make landfall. If not, we were looking at two thousand miles of open water to the Azores or Plan B, which was a downwind run 20 miles to Cape Cod.

Given the wind direction, it was clear that we weren't going to make the landing in relation to where we needed to go. Jeremy suggested we tack and attempt to make up some ground by heading back towards Muskeget. Turning around, we sailed back over the shoal and beat our way across the wind trying to get ourselves a better shot at making the harbor. The suggestion was made to reef the sail so we turned into the wind, only to find we were losing all the gains we’d made by getting dragged backwards with the current and wind. We got back on course and Jeremy pinched as much as he could out of the wind and tide. It looked like our plan was working. We were now on a direct line to the outer beaches of Coatue on the northern shore of Nantucket, about five miles south of the Great Point light, but five miles past the harbor entrance. That was fine by us.

We sailed straight into the beach, rolling the boat up high and out of harm's way and celebrating our amazing day with a round of high fives.

It looked as if the rain was about to return so we pulled a tarp up over the leeward ama and made a shelter to hide out in. Jeremy, having stripped down to his shorts, said “I'm going to go for a run and check this place out!” Then he turned and took off running down the beach toward the light that we guessed was about six miles away.

While Jeremy went for a run, Will and I set up the stove and boiled some water for coffee, hunkering down out of the rain. About an hour went by and the rain was now coming down in sheets. We laughed at the thought of Jeremy out there in only his shorts. After a while we began to wonder where he was. Fifteen minutes later, Jeremy jogged into camp carrying a football and a small orange device.

“Where'd you go man? Did you make it to the light?” Will asked, laughing.

“Almost! I wanted to but I ran into these gnarly seagulls! They were acting really strange, unlike any seagulls I've seen before so I bailed. I thought they were going to attack my head! But hey, I found a shark tracker!” Sure enough, the orange object he held, upon closer inspection, was

Indeed a shark tracker. A tiny label encased in resin read, Shark tracker, Please contact the New England Aquarium if found. The waters north of Nantucket host one of the largest seasonal communities of Great White sharks on Earth and it was exciting to hold something that had possibly been carried around for years by a Great White while it was being tracked by scientists. (Later we discovered it had been on a sand shark, another species the lab was monitoring. Bummer.) After admiring the shark tracker, the three of us sat under the tarp reflecting on the day and hiding from the rain.

All of a sudden in the silence a voice boomed, seemingly out of thin air, “You guys OK!?”

All of us jumped, not expecting to see anyone out here. It was a ranger for the Trustees, an organization that controls and maintains the land we were on,which turned out to be a wildlife sanctuary.

We looked over to see another ranger, a young man in his twenties holding a radio. He was staring at us with eyes the size of plates and his jaw dropped. His look was one of amazement as if he was witnessing a real life shipwreck and we were some castaways that had washed ashore after weeks at sea.

“Yeah!” We said, “We just sailed in from the Vineyard during the storm and overshot the harbor so we're just hiding out until the storm passes!”

“Oh, OK then!”

Later the rain lifted and we took the opportunity to explore the beach, discovering multiple decomposing seal carcases and dozens of nesting seabirds. A quick hike across the barrier island revealed that we were not alone. Not three hundred yards from where we had set up our shelter, there were people blowing up kites on the beach, having boated out from town. Even more people were in the water kiteboarding in the calmer waters that this small spit of land had created out of the wind. Amazing.

We had just come off the water from what could have been a pretty serious situation, set up camp where we entertained the idea of spending yet another night, and were on a deserted beach that could have been in Namibia or Baja California, covered with rotting seal corpses and wild birds. Yet we were on one of the most expensive, exclusive islands on the entire planet. We thought about it. We had just spent the last four days traversing one of the most densely populated areas of the United States during peak summer season. We had done it alone, in a 3-man outrigger canoe. We had camped on wild beaches every night of the trip proving - once again - that adventure doesn't require international travel and a bus full of gear. Most times, it can be found by simply stepping out your front door and looking at the world with a different perspective.

At about four o’clock, we weighed our options and decided that hot food and beds sounded better than another night in the sand, so we pushed the boat back into the water and paddled off the beach towards town, against the current again, but in the lee of the wind,

We covered the four miles in about an hour and a half. There is a break in the east jetty of Nantucket for boat passage and thankfully it was wide enough for our fifteen feet of beam to pass through, saving us another two-mile trip around the jetties.

A short blast across the harbor had us stepping off onto solid ground for the last time on our journey. This was the end. From here we would scatter to our homes again, and take up the details of our daily lives. Tracy was there to greet us, and she and I drove home where I grabbed my car and headed back to pick up the guys for much needed warm showers, hot dinner and comfortable beds.

Every inch of water, wind, rain, shoals and storm had been so worth it; an unforgettable adventure.